Monday, 10/20

This will be my final update here, although there are still a number of films I hope to catch online and I'll be sure to include any highlights from those in future coverage. This was a pretty darned successful festival on my end— I didn't see anything that was an outright failure, even if it wasn't all necessarily my cup of tea, and most everything I did see was at least pretty good. My favorite was the delightfully creative documentary Niñxs, which found a new way to tell an important human story, as was entertaining as heck, to boot. Here's a look at yesterday's screenings:

Beautiful Evening, Beautiful Day

Taking place in Tito's post-war Yugoslavia, here is a film about filmmakers, a film about artists in a society that seeks to exert complete control, and, importantly, a film about gay men in a world that inflicts harsh penalties on them for being who they are.

When film director Lovro and his crew (including his screenwriter and romantic partner) receive the attention of the country's Communist government for daring to shoot a scene that might, possibly, kind of, maybe if you look at it from a certain angle, show a Yugoslavian soldier abandoning his post ("It's ambiguous!" Lovro insists, though there's no room for ambiguity here, and we see the trouble it can cause), their film company is taken over by the government's Agit-Prop office and forced to shoot propaganda showing happy workers supporting the country and its aims. A man from Agit-Prop is sent to oversee it all and, secretly, to sabotage whatever the film company is doing. Lovro has a friend in high places, so it seems the government doesn't feel comfortable simply shutting him down, but that kind of safety only lasts as long as it can.

We're given a long and serious look into just how overwhelmingly controlling Tito's regime is as we see households being forced to live with strangers, workers being moved to other cities to take other jobs because of petty (or sometimes nonexistent) reasons, people being given "stamps" each week that allow them to buy only certain things (one woman desperately hopes for stamps to buy shoes as she's handed a couple for pantry staples and nothing else), and how everyone has to worry about the person next to them telling the government about every little thing they do that might raise suspicion of a person not being loyal to the cause. When Lovro's company is taken over, the Agit-Prop minister makes a show of creating an "executive committee" that will determine the direction of filmmaking, a committee that will be made up of people from all walks of life, everyone being equal, of course. He chooses himself, a cleaning woman, and a lighting technician, and then basically never mentions the committee again (the cleaning woman, now with such a prominent position, is the one who dreams of new shoes, so we see where that got her). The bureaucratic control even extends into the afterlife, as one old woman wonders what will now happen to her dead husband: "Are the dead coming back because the Party canceled Paradise?"

But this isn't all we see. Lovro and his crew are clever, and we begin to discover how they're exerting their own creative control in this completel restrictive situation. And in this way the movie becomes about some kind of creation, and the extraordinary lengths people will go to creatively to express themselves to whatever degree they can. And through this, the propaganda minister also begins to see Lovro and the filmmakers as people (it helps that they save his life after he secretly sets fire to all of their film canisters), which is eventually crucial to their survival.

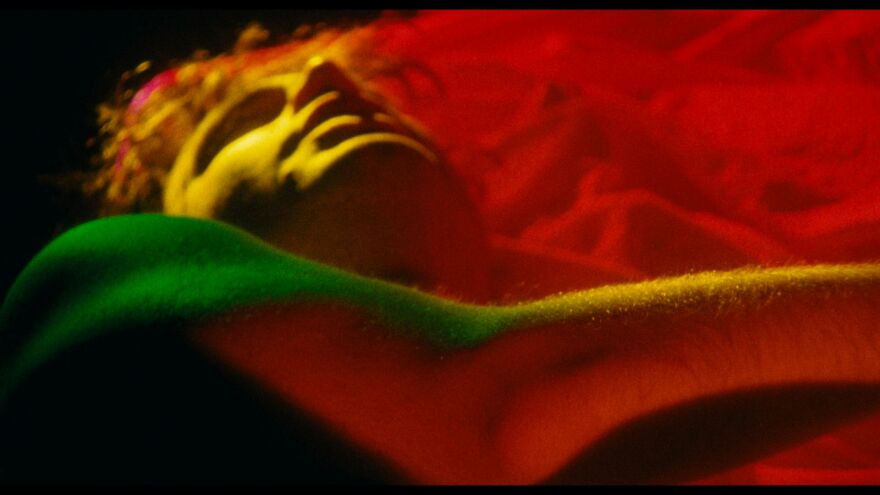

And this, of course, is because the filmmakers are gay, and we hear horrifying tales of gay Yugoslavians being sent to an island prison from which they never return. Which all adds just one more layer to their story (although it may be the most important layer), as they have to keep their true selves hidden even though most people generally know they're gay (it's as if the regime is just sitting there watching and waiting for one of them to slip up and let it out in the open so they can pounce). The movie includes a number of quite explicit sex scenes between the men, which often serves the purpose of reminding us that this is not an abstract situation— these are their lives that we're seeing. As we might expect, there's not exactly a happy ending coming (this is an understatement), although exactly how things play out becomes slightly ambiguous itself, leaving us just a little room to acknowledge the place of hope in an otherwise suffocating situation.

WTO/99

There will be too much that's far too familiar here. Which I say only as it regards your comfort level, not whether or not you should see the film. Because we need things that make us uncomfortable.

Whatever else this movie is (and it's much more than just this), it's a pretty incredible feat of editing— it follows the few days in Seattle in 1999 when thousands of people clogged the streets to protest an international meeting of the World Trade Organization, and it's made up almost entirely of archival footage from protestors shooting their own videos, from news organizations, and from other independent journalists (there are occasionally title cards providing a bit of context and placing us at certain times of the day). And seeing all of this now, knowing where we are in 2025 is fascinating and distressing, and it all seems as if it were inevitable.

I won't rehash the details here— this was hardly the first time a police state was used against people on the streets of the United States, but the growing importance of portable recording devices (smaller and smaller video cameras at this point in time) in documenting the situation becomes so clear in seeing these images, and especially as we see the increasing militarization of the police and law enforcement. But of course this is hardly all of it— we can also see all of the disparate interests and movements that came together to oppose the WTO (and how they were hand-waved away by the very powerful), and we can follow the path from where they were in 1999 to where many of them are now, split into completely opposing camps, each reaching very different conclusions after being on the same page for at least this one issue (it's acknowledged many times in the film that a lot of the groups and people opposing the WTO had essentially no common ground otherwise, which we can see as Alan Keyes and Ralph Nader are on the same side here). We're hardly looking at a moment in time as we watch this film— we're seeing everything that came before and, unfortunately, everything that's come after.

Abigail Before Beatrice

I need to know more about cults. Not because I want to (I don't, really), but because I never really know whether a movie is depicting how any cult actually operates or whether it's largely a product of the filmmaker's imagination (and other movies about cults). Not that it matters a whole lot, fiction is fiction, it can be whatever it wants. Still, I wonder.

Regardless, Abigail Before Beatrice does take an angle we don't see so often, in that it shows us a woman who's still a true believer even after her cult has dissolved, who still thinks she (well, her cult leader) had it right all along. Our expectations as movie-watchers lead us to assume the person at the center of a film is the one who has made positive change, or will soon. It's disconcerting when that person is the opposite, is still holding tight to some horridly wrong idea, even when other around her have made the change we expected from her.

And this is much of the point, of course, to make us uncomfortable and to confront us with this difficult situation, to challenge what we expect and what we think we know. And even if this film doesn't do all of this entirely successfully, I appreciated the idea.

It doesn't seem fair to try to outline the plot here, although I've already somewhat spoiled what becomes clear to us as the movie goes on. Beatrice (not her real name) seems rudderless as she appears one day in a family's garden, and we learn over time that her lack of direction is because she's waiting for the man who led her cult to be released from prison. (This has nothing to do with anything, but the guy looks exactly like Shea Whigham and Daniel Radcliffe had a baby and the baby grew up into a man.) We also, eventually, meet a woman who was with Beatrice in the cult, but who has quite obviously thought better of the whole situation.

It does all seem obvious to us, of course, that Beatrice is so wrong-headed, and so I do wish we could see more of an effort to help us understand why she is the way she is (there's a brief stab at it near the film's end, but it's sort of what we expect— she was vulnerable and the man took advantage of that). And this is part of why I'd like to understand cults a little more, because often, our movies aren't providing that for us. As suspense, what we find from this film is not too bad, although the performances, especially from the men, feel as if they're playing one note at one volume. As something more than that, we're left wanting. Or, at least, I am.

Sunday, 10/19

Seeds

There's a moment about halfway through Brittany Shyne's documentary when we catch a faint glimpse of the camera operator (maybe Shyne herself) in the reflection in a pickup truck window, and I thought how odd a decision it was to keep that shot in the film, since we hadn't acknowledged the filmmakers at all up to that point, with the movie's style designed to appear entirely observational, without interviews or the subjects addressing the camera. But we stay in the back of that truck with a young girl as she takes a short ride to another part of the farm she's on, and as we move, she smiles at the camera a couple of times. And then I realized how smart it was to include that first shot of the camera operator, to prime us for the fact that this girl was going to be acknowledging that we (or, the camera) exist and she's going to look at us in a way no one else does in the film. Yes, Shyne could have cut both scenes from the movie, but the girl smiling is irresistible, and if she was going to include that, also including the initial shot was a magnificent touch.

I mention this just to illustrate how intelligently and intentionally Seeds is shot and edited as it tells its story of generations of Black farmers in Georgia— it's at turns impressionistic, political, and contemplative, and always gorgeous. The movie's already won a Grand Jury Prize from the Sundance Film Festival and may have more awards in store, particularly for its beautiful black-and-white photography, which is understandably what most people will remark on.

A lot of the movie is made up of the farmers at work, with their families, simply living their lives, although those lives are not the easiest— one old man struggles to pay for the glasses he'll need, many of the farmers are working far harder and longer than a person ought to have to at their ages. But we also see just how important this all is to many of them, and especially as it concerns future generations and their provenance and legacies, not to mention their more concrete lives and way of life. We hear one farmer talk about how people tell him he looks too young to have great-grandchildren, and he does, but more importantly, we then see how much those great-grandchildren matter to him and what he's trying to maintain.

We also see, crucially, the struggle these farmers experience while trying to receive government support that's already been approved for them (passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden) but that still hasn't been distributed months later. This, despite the fact that white farmers had no such difficulties receiving aid. As one farmer is told (paraphrasing), "we know it's always been this way for Black farmers— the white farmers will sue."

Not every single move Shyne makes works, there are a few occasions when we're provided a kind of ethereal musical score over what we're watching, and while this seems like something that might work in a film like this, it happens rarely enough that it ends up distancing us from what we're seeing instead of taking us deeper into it. When we're watching the farmers work with their enormous machines the effect is mesmerizing enough, we don't need the artificial help provided by the music. But any complaints I have are obviously small— this is really a very, very good piece of work.

Niñxs

This is the second documentary I saw today that was shot over the course of nearly a decade, and it's one that I don't think I would have even been sure was a documentary had I not read a bit more about it after watching it, the style is so unusual. It's also a little bit magical.

We open with the movie's director, Kani Lapuerta, and its subject, Karla, talking in voiceover about how to start the movie and how to tell its story. Karla says it's probably best to start from the beginning and tell us what happened up till now, rather than going backwards. And so that's mostly what we do. A lot of what we see looks like it's manufactured reenactments of what might have been real events and situations, and some of this has to be true, although that doesn't necessarily make it any less real (talk to Werner Herzog about manufactured situations in documentaries), and this is partly what led to my confusion about the nature of the movie itself, which I don't bring up as a criticism, but simply to note that this is not a movie much like one you've ever seen before. Karla and Lapuerta jump in with their narration throughout the movie, as they evaluate what they're showing us and rethink how they're showing it to us. It's a clever and entertaining device that's probably borne from a couple of things— one, this is Lapuerta's first movie, and he admits he didn't really know what he was doing when he started it, which likely freed him up to do pretty much whatever seemed right at the time and to try things that a person with more experience might not even think of. If you don't really know the rules, you can do just about anything. Second, this approach created a wholly collaborative film, with Karla having clear and constant input into the shape and direction of the movie.

And this second part is incredibly important, both to the film and to Lapuerta. Because Karla is a trans girl, and Lapuerta is a trans man, and the director says he hasn't seen nearly enough trans people being able to tell their own stories— they're always having their stories told for them, and often by cisgender filmmakers. Opening us up to seeing a young trans girl (Karla was around seven when the filming began and around 15 when it ended) tell her own story in the way she wants to tell it is drastically important, both to telling the story in the right way and to helping us understand the feelings, thoughts, and agency of young people, people who are rarely perceived as having whole lives of their own. Moreover, Karla's parents are almost entirely supportive of every part of her, and Lapuerta notes this is also something we rarely see— so many trans and queer stories focus on struggles and difficulties with families, which are real and far-too-common stories, but they aren't the only stories. What we end up with here is a film with enormous creativity and life, and one that is, importantly, life-affirming.

(Niñxs plays again today at 11:00 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

Saturday, 10/18

Diamond Diplomacy

I write this mere hours after Shohei Ohtani became the first player ever to strike out 10 batters and also hit three home runs in a single game, as his Los Angeles Dodgers return to the World Series. The Dodgers, interestingly, also being the team that signed Hideo Nomo in 1995, after decades of Japanese players not being allowed to play Major League baseball.

This fairly straightforward documentary takes us through the history of Japanese baseball, and especially as it relates to American baseball, as the two seem to be entirely intertwined— we learn Americans brought baseball to Japan not long after the U.S. Civil War and the end of the Japanese Edo period, and that Japan became at least as baseball-crazed as Americans were, if not more so. And we see how, for many years, American teams would travel to Japan to play against local teams in front of massive crowds, including Negro Leagues teams, who would be received far more favorably than they were in their own country. We see the effects of World War II, Japanese internment, the post-war period, and so on.

I enjoyed the heck out of this. I'm also a huge baseball fan, although there's enough here with social and historical context that I wouldn't have to be. Talking heads from both sides of the Pacific tell us about what's going on, about how baseball meshes so well with preexisting Japanese culture, providing context for events many of us might not have realized ever occurred. And there's a ton of fantastic archival footage, some of it of shockingly good quality (I'd like to know more about this) that is catnip for someone like me. Admittedly, there are some voiceover reenactments of words written by famous people that are a little bit goofy, but we can make allowances.

Shohei Ohtani bookends the film with his appearance in the recent World Baseball Classic, but very little of the movie actually takes place after the 1960s, when Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese player in the Major Leagues and then had to return to Japan a few years later, setting off the "ban" on Japanese players in American baseball. And this is fairly surprising, given Ichiro is coming. The man gets his mention, we see him enter the Hall of Fame, but many recent events feel crammed in during the last few minutes, and at 80 minutes, we wonder why this is the way they went. Or maybe I just wanted to see more.

(Diamond Diplomacy plays again today at 2:30 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

It Comes in Waves

There are times you see a movie that doesn't quite get there, but that shows so much promise from a new director that you can't help but be excited about what they might do next.

This is the first feature from Haitian-Canadian director Fitch Jean, and it follows Akai, a young man whose family fled the Rwandan genocide for Canada, and his efforts to care for his younger sister following his father's death and his mother's clear difficulty in recovering from the horrors they experienced. And there are times Jean has an excellent command on the film's tone, as we understand how insidious trauma is even when a person is (largely) otherwise safe, and how its tendrils sometimes never let go. This is especially true in the first 30 minutes or so, as we see more of Akai's mother and how extremely, painfully hard it all is on her, before Akai has to go to great lengths to care for his younger sister and figure out some way to ground himself in his current reality.

Adrian Walters, who plays Akai, has an obvious ease as an actor, although this comes through most when his character is at ease, with his instantly comfortable smile and natural charm. It's less true when he's stressed, which is most of the movie, not that he struggles to play the part, but more that some of what happens feels forced, and this becomes true for the film itself. The score is occasionally overbearing, as if we need to be told that what's happening is dramatic, and things just get a little bit weird after a while, with some strained emotion and a character who more or less just appears out of nowhere to help Akai work through some things.

Still, what Jean does with the most successful parts of this movie are kind of exciting— when he does find his handle on the movie's emotional core (it sometimes feels like it's wiggling in and out of his grasp) it's truly affecting, and we know that if he can find a way to sharpen his focus as a writer and a director, there may be great things in store.

(It Comes in Waves plays again Sunday at 2:15 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

Anything That Moves

All right. Look. As far as absurdist fever dreams about sex workers shot in a throwback style that are playing at Tallgrass this year, I acknowledge that F*cktoys is far more my speed. Not all movies are for everyone, and this one is for a very, very specific audience. That specific audience will absolutely eat it up. Me? Not for me.

But, I do admire its commitment to the bit. Liam is a bicycle deliveryman who delivers sex to people who buy it using a handy phone app. His girlfriend works with him, and they fulfill all kinds of fantasies for other people, fantasies that are meant to seem outrageous or absurd, but I'm certainly not judging anyone who enjoys any particular one of these things. Well, I am judging the serial killer who seems to be following Liam and murdering his clients by digging holes into the backs of their heads. I feel comfortable saying that's a line that shouldn't be crossed.

There's a lot (a LOT) of sex, which of course needs to be in movies more than it is, although I found myself quickly (very quickly) getting bone-crushingly bored with what was happening on screen, despite the movie's efforts to do the opposite to me (I think? I don't actually know what its aims were here, but it's trying VERY hard). The story is purposely difficult to grab hold of, which isn't so much of a problem, except that I already had trouble maintaining attention, and the 16mm cinematography is quite fun to look at, especially with the film's highly fractured editing, and this all would have made for a relatively entertaining short film, had they decided to go that route (80 minutes is short, but still to long for me in this case). Having said that, the cumulative effect of the movie, holding so tightly to this vision of what the director, Alex Phillips, wanted, would not have been reached at a shorter length. So, again, I have to note that this is not for me, but the movie, as it's made, is unquestionably for someone, and that someone will be very, very happy.

(Anything That Moves plays again Sunday at 5:30 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

Friday, 10/17

Coroner to the Stars

We all have our favorite medical examiners from our favorite crime shows— mine, of course, is a tie between Dr. Cox on Homicide: Life on the Street and Woody from Psych— and as far as this documentary is concerned, few people are more responsible for us even knowing or caring what a medical examiner is than Dr. Thomas Noguchi, the former Chief Medical Examiner for Los Angeles County. Noguchi oversaw autopsies for a number of luminaries (Robert Kennedy, William Holden, and Natalie Wood among them), apparently inspired the creation of Quincy, M.E., and became a minor public figure in his own right as he informed the press about the results of high-profile autopsies.

The film takes us through Noguchi's life, telling us he grew up in Japan before moving to the U.S. in the early 1950s (as he tells it, he liked the idea of living in the place that defeated the previously unconquered Japan in war) and taking a job in the M.E.'s office in Los Angeles, eventually rising to become the head of the department. Fortunately, Noguchi is still with us, so we're able to hear his own words, but we're also given a number of the usual talking heads (mostly other medical examiners) and plenty of archival footage from the doctor's time in his position.

The most compelling parts of the film involve Noguchi's troubles with city government as on multiple occasions he faced accusations of mismanagement of his (severely understaffed department), and through these events we see Noguchi dealing with possible racial discrimination and, especially in the early 1980s, the heavily politicized nature of anything involving municipal governance, and very definitely when it also involves the image of major Hollywood stars. The movie is clearly on Noguchi's side in these matters (it doesn't try to hide this), although I'm obviously in no position to say one way or the other how much it reflects the true nature of what happened (like most things, the answer is probably, "it's complicated.")

The documentary has at least one glaring and irritating stylistic crutch, namely, a near-constant musical score that sounds like the "suspenseful" part of any true-crime documentary, at least until the very end, when it becomes more "contemplative." It's unnecessary and makes us feel like the filmmakers don't have enough confidence in their subject and want to inject extra drama. I don't believe that's the case, I think they do feel their subject is interesting enough to carry the whole thing (heck, they made an entire movie about him), but that's the ultimate effect, and it's unfortunate.

(Coroner to the Stars plays tonight at 8:00 at Century II's Mary Jane Teall Theater.)

Rosemead

Most of the talk around this movie is going to focus on Lucy Liu, which is justified, as she gives an excellent performance in a decent enough movie. I don't really remember ever seeing her in such a weighty dramatic role, and I don't know if that's because she's never had a real opportunity at one or if it's because she's simply grown into the ability to perform at this level, but whatever the reason, she's fantastic here.

The movie is supposedly based on ("inspired by") a real story, and it's a deeply sad one. Liu plays Irene, who's an immigrant from Taiwan living in the title city in Los Angeles County with her 17-year-old son, Joe. Her husband, Joe's father, died not terribly long ago, and that's compounded the huge problems already presented by Irene's cancer and Joe's schizophrenia.

As the film goes on, Joe's mental health difficulties get more intense and Irene begins to worry that he's going to do something violent as she discovers he's been spending a lot of time reading about school shootings and looking at guns on the internet. And I worried that the movie might be perpetuating an assumption that people with schizophrenia are prone to acts of violence (even while a therapist in the film tells us this is extremely rare, and as we, ourselves, know people with mental illness are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators). But, fortunately (if any event in the film is fortunate), there's never any true indication that Joe intends anyone any harm.

Still, where it all ends up it incredibly painful, and we understand the context surrounding it all far better than if we were to read a news story about what eventually happens. Liu shows us all of the confusion and turmoil Irene is experiencing as this all goes on, and she does it with an expertly physical performance, altering the way she walks and making her face fall progressively farther and farther as the film goes on. Much of how Irene handles everything is informed by her cultural context, and seeing this helps us understand her actions, to the extent that we can (and, it turns out, we can understand far more than we might have expected). Joe's condition is presented to us through fragments of images and sounds, and we can understand there, too, what motivates him to do the things he does. If movies are meant to help us have empathy, Rosemead gets us a lot closer to an unimaginable situation than we might have thought we could ever be.

(Rosemead plays today at 5:00 at Century II's Mary Jane Teall Theater and again Sunday at 2:15 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

An Autumn Summer

Ah, youth. It's hard to depict accurately on screen, and An Autumn Summer doesn't quite do it. But! It does some other things well, and if nothing else, it gets by on vibes.

It's the end of the summer after high school, right before college, and Kevin and Cody and Jared and Martin are staying with Kevin's parents at a cabin by a lake. Kevin and Cody are dating, and they've all been friends for a very long time, although they're about to scattered to the four winds as they head off to new lives.

And this is largely where we are for the whole film, with the friends being friends, with Kevin and Cody simply being as with each other as they can while also knowing a seismic change is coming, and with the cadence of summer winding down. There's no defined narrative arc to speak of, which is the way it needs to be, because if anything doesn't have a real narrative arc, it's the end of summer, that particular summer, with those moments when one life is ending and another is beginning.

I say the film doesn't quite get youth right, and what I mean is that it doesn't quite get the speech, the way people really talk to each other. These are smart kids, and so it wouldn't be right to say they're too articulate to feel real, but the ease with which they're articulate doesn't reflect the true rhythms of being this age, or of being deeply, confusingly human. (I contrast this with Cooper Raiff's Sh*thouse, which gets that part of things so right that it's sometimes uncomfortable.) The kids aren't glib, there's feeling and meaning behind what they say, but they're written, and sometimes overwritten, enough so that it distanced me from any kind of true connection. Still, some of the ideas are just right, certainly with how they interact, and even with what they express (if not the way they express it)— there's a moment when Cody is reluctant to jump from a high rock into the cold water and she says, "When you're 14, this is like whatever," meaning that things were so much easier when she was younger, as if being 18 were so drastically different, which it is, especially when you're 18. And if the rhythms of the dialogue are wrong the rhythms of the filmmaking is far more right, with the lush photography and deliberate editing keeping us right in that late summer place partway between being asleep and being awake. And while most of the film is generally what you expect from something like this, there is one specific, short moment when Cody and Kevin are together that is stylistically far out of place with the rest of the movie, but it's the kind of thing that makes you appreciate the artistic risk, and that reminds us there's always a little surprise even in those things we think we already know.

(An Autumn Summer plays again today at 2:15 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

Thursday, 10/16

It's Dorothy

This says more about me than it does about anything else in the world, but I still have some moderate amount of guilt that I was once late to a T-ball practice in 1985 because I had my dad take me to see Return to Oz for a second time and we didn't tell the coach that's why I was late. It wasn't even the first time I'd seen it! And we knew we'd be late! Simply shameful.

But while I grew up in Kansas, and Wizard of Oz references are, of course, unavoidable (basically, you tell people you're from Kansas and they ask about The Wizard of Oz first and then they ask if people in Kansas actually ride cows in the street, or at least this is what happened to me at a baseball game in Cleveland one time) I've never had much connection to the 1939 film, which I acknowledge is glorious but which I've never felt any emotional attachment to. I have my own young children now, so maybe this will change, but then again, maybe not.

(For what it's worth, Return to Oz is a different story, I've loved it and been terrified by it since 1985, and watching it as an adult I kind of can't believe I took to it so well, it's truly frightening and I was not exactly a bold kid with a robust courage.)

As if it needs to be said, though, a lot of people do have a deep connection to The Wizard of Oz and Judy Garland in her ruby slippers, and to Diana Ross in The Wiz (which, frankly, I also remember better from my childhood), and Jeffrey McHale's documentary tries to tease out exactly what's so enchanting and captivating about it all. He lands on Dorothy, as a character, as the overarching factor that pulls us all in, or at least Dorothy's experience and what it says to all of us about our own places in a sometimes strange and unforgiving world. McHale presents us with a number of different actors who've played Dorothy in various adaptations (films, Broadways productions of both The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz, even Muppet movies), each talking about who Dorothy is and how she spoke to each of their lives. And while we hear the voices of quite a few others— scholars, artists, descendants of L. Frank Baum's— the Dorothys are the only faces we actually see interviewed on screen. Not a bad touch.

There's a whole lot of archival footage, of course, which is necessary given how much attention is devoted to Judy Garland, and we're most absorbed when the movie turns to Garland and her life and struggles and place in cultural and social history, and the film sometimes sags a bit when we hear from some of the others. This is hardly their fault, of course— few other people are going to seem as compelling when we could be hearing more about Judy Garland. Outside of Garland, we do at least get some examination of The Wiz and its rather tepid reception from the largely white critical community, although I'd be interested to see a sharper take on all of that (not a place this movie was ever going to go).

I'm not completely sold that the film makes its case as well as it would have liked to, but I'm also probably not the one it's making its case to— Dorothy does mean a lot to a lot of people and the film has the best of intentions, which can take you a long way.

(It's Dorothy plays tonight beginning at 7:30 and 8:00, both screenings at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)

F*cktoys

Before watching this, I happened to read yet another article with some joker insisting AI is going to make real filmmakers and artists obsolete, and the main thing that ran through my head while the movie played was this:

AI could never.

This is true both of the good things and the bad things about F*cktoys (the title doesn't actually have an asterisk in it, for what that's worth, but we'll keep this post PG-13, although I recently discovered you can actually say that word more than once in a PG-13 movie now, which surprised me and which also kind of neutralizes a pretty good joke in John Waters' Cry-Baby), but as someone who values film as art, even when it's (intentionally) trash art, I find it thrilling when you can clearly tell this is exactly the movie the filmmakers wanted to make, even when parts of the movie aren't, themselves, all that thrilling.

Annapurna Sriram wrote, directed, and stars in the movie, which opens with her character being told by a psychic that she has a curse on her, and that's why bad things have been happening to her, she's been getting progressively sicker, her hair is falling out, that sort of thing (she seems fine, but for this movie, that's also fine). Getting the curse lifted will cost her a cool grand, so she gets a second opinion, and then another couple opinions, and yeah, pretty much everything thinks she's cursed. C'est la vie. She's a sex worker who specializes in... well... it seems like she specializes in something, but it's really not clear what that might be, her clients are all over the map. She reunites with an old friend, the two take off on adventures (sort of), and if there's a really strong narrative it either doesn't really matter or gets a little bit lost, but it's hardly the point anyway. The movie's shot with a handheld camera and enough lens flares to make J.J. Abrams drool, there are occasionally people in hazmat suits (some of whom have water coolers on their heads?) cleaning something at the side of the frame, there's chaos and silliness and grotesquerie galore, and while it doesn't all hit, it's a heck of a lot of fun to see someone just let the firehouse of their imagination spew out whatever it can.

The movie's momentum also drops, hard, about a third of the way in and it never recovers. Things do, also, eventually get far more serious, and this might be part of why we slow down so much, but it does become a problem. Without giving anything away, by the end we wonder a bit why we've spent all this time doing all this, especially as even the movie itself seems to have an ironic detachment in its most deadly serious parts.

But— and this is important— these are flaws created by human beings. These are human ideas that simply aren't perfectly executed, but we can have no doubt that a person was behind them. There's passion and creation, there's a spark of life and strangeness and surprise that we know can only come from that certain thing inside us that makes us human. Come on, that's why we love the movies.

(F*cktoys plays tonight at 10:15 at Boulevard Theatres in Old Town.)