WICHITA, Kansas — Open the newspaper to the obituaries and you’ll read a reflection of our times.

Private family graveside services planned. … Celebration of life at a later date. ... The memorial service will be live-streamed.

Across Kansas, people find themselves searching for ways to grieve for, remember and celebrate the lives of their loved ones that have died, all during a time when they aren’t allowed to gather in large groups.

School buildings are closed. People are setting aside sports, concerts and church services. Some work from home. Kansans are effectively living under a statewide pause order from the governor. But some are learning the harsh reality that you can’t put a pause on death and the grief that comes with it.

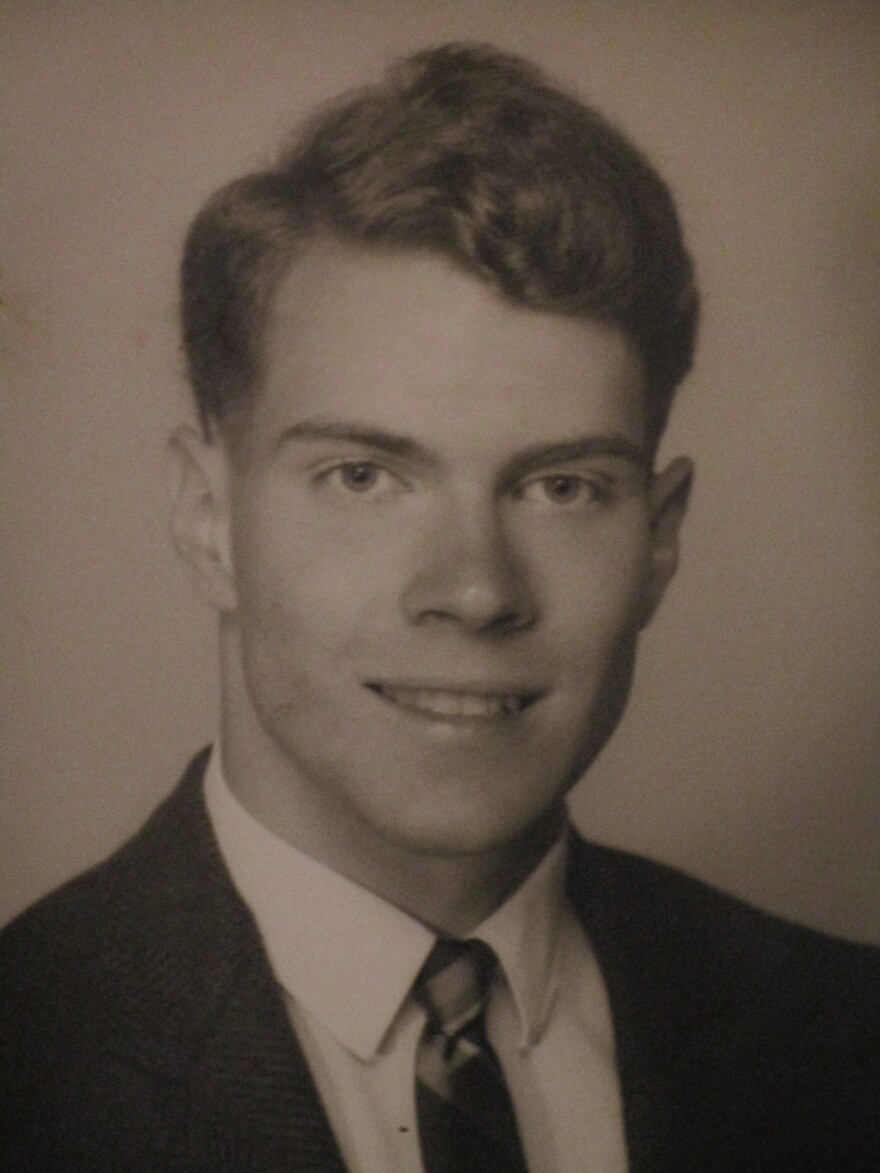

Funeral planning had fallen to Michael Webb, an economics teacher turned caregiver and grant writer from Wichita, when his mother and father died years before. But when he lost his brother, Alan, about two weeks ago, the funeral home told him only 10 people could be there — Webb and his wife, six pallbearers, the minister and one lone guest.

“That’s not the funeral that my brother would want,” Webb said. “That’s not the funeral his friends would want.”

He ultimately decided to delay the funeral and only have a small graveside service, again, limited to 10 people. The cemetery told him the only available time they had was 4 days after Alan’s death, and they’d only be able to put out one seat.

“Alan deserved a really nice memorial service where his friends could come and celebrate with him,” Webb said. “And we will be planning that, we just don’t know when it’s going to be.”

Because of the limit on the number of people who can gather, Webb’s stepdaughter could only stand on the side of the road and wave goodbye as the casket left Wichita headed for a burial plot in Topeka.

“Some immediate families are over 10 people, which creates some problems,” said Pam Scott, executive director of the Kansas Funeral Directors Association. “(Funeral homes) are doing all they can to work with the families, and most families have been understanding.”

Funeral homes and mortuaries are deemed an essential service and are exempt from the governor’s stay-at-home order, but they still need to limit opportunities to spread the virus.

“It’s the unknown factor,” said Mack Smith, executive secretary at the Kansas Board of Mortuary Arts. “And funeral homes sure don’t want to have any of their people getting this nasty thing and spreading it to others.”

He said the agency has received a few calls from people upset or confused by the restrictions.

“Change is tough for a lot of us,” he said. “And not being able to sit down in a chapel and say goodbye to mom or dad or a friend — that’s a tough thing to do.”

Even alternatives such as delaying a service, maybe for months, can prevent people from fully grieving. Mary Rush lost her father right at the beginning of the outbreak in Kansas. Because her siblings live outside of the state, including two in Europe, it was impossible for them to get together — and phone calls just didn’t cut it.

“That peace is missing for us right now,” Rush said. “I don’t feel the impact of that every day. But it does come from time to time.”

The desire to slow the spread of COVID-19 hinders people who want to comfort those in mourning, too. At Chapel Hill United Methodist Church in Wichita, the Rev. Jeff Gannon has had to work with grieving families over the phone, rather than his customary home visits.

“Normally, it’s face-to-face where I sit down with families and together we talk through the service and we plan and we cry and we laugh,” Gannon said.

Now, he and others wanting to provide comfort must be more creative. For him, that means sending a card, making a phone call, or maybe even simply saying a prayer. But he suggests it’s those kinds of things, even if imperfect or incomplete, that can fill grieving people with the hope needed to make it to the other side of a tough situation.

“Call it intuition, call it the Holy Spirit, call it whatever you want,” Gannon said, “but I urge people to follow up on those nudges, because more often than not that’s a way to connect at the most important time.”

Brian Grimmett reports on the environment, energy and natural resources for KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @briangrimmett or email him at grimmett (at) kmuw (dot) org. The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.