Hey there, everyone! I’ll be updating this page through the course of this year’s festival—I’ll leave this welcome message here and update below, most recent posts at the top.

I have bad and good news: the bad news is that I applied to cover this year’s festival remotely, but not too long before the festival they changed course and decided nearly the entire thing was going to be held in person. Fun for physical festival goers! A little disappointing for those of us who expected something else. But there is a silver lining—most of the movies available to those of us covering the festival remotely are films with not as high a profile, which means I’ll be checking out movies I might not have otherwise. Yes, we’re all excited about the Coens and the Campions and the Almodóvars, but I’ll see (and cover) all of those eventually anyway. We’ll hear plenty about them. This gives us a chance to explore some stuff we might not have had time for if we’d been watching those, and also to catch up with some of the incredible restorations and revivals of older films the festival is showing. I admit sometimes these are things that get squeezed out when I’m off chasing the shiny object. This forces me to dig a little deeper, and hopefully be a better movie lover.

OK, here we go! New York! (From my home!)

Friday, 10/8/21

Parallel Mothers

And so, the festival closes with Pedro Almodóvar and one of the best movies of the year, which are a couple of things we often find in the same sentence. Still, this one floored me.

One of the mothers of the title, and the one we are with most of the film, is Penélope Cruz (simply magnificent in this role), a woman nearing 40 and having a baby on her own, after splitting with the man she was having an affair with. That man is a forensic anthropologist who is helping Cruz locate the remains of her great-grandfather, believed to have been murdered during the Spanish Civil War. You might imagine we return to that. Cruz’s roommate at the hospital is a pregnant teenager, Ana, also about to be a single mother, and the two women bond over their shared experience as they have their children at roughly the same time, have to wait a bit longer than they’d like at the hospital as their babies get over some health issues, and as they both leave to begin their new lives as mothers.

As things often do, it all gets more complicated than this (in ways things often don’t do), and Almodóvar’s ability to layer so many incredibly complex feelings and events on top of each other is almost impossible to believe. Any one of them would make up the entire plot of another movie. There are a number of tiny details and enormous twists of fate that are gut-punches, and there are times we feel two, or even three different ways about what’s happening. But because Almodóvar treats his characters with such empathy, because he genuinely cares about the women who are so often the focus of his films, we can understand how conflicted Cruz, especially, must feel about what she’s experiencing—her head is swimming, but so is ours, and so we’re there with her, instead of just watching her. In some other world, this movie could be a caper or a fiasco or a bizarre psychodrama, but Almodóvar has so much love in his heart that we get real people dealing with difficult truths.

And those difficult truths are things we have to confront in this life, which does, eventually, bring us back to unearthing those graves. Much of this movie is about having to acknowledge realities that seem unbelievable, and figuring out how to move forward, however painful that might be.

(Also, can I just say for a second how nice it is to watch a movie by a true filmmaker? It looks incredible and flows so well, because Almodóvar knows just where to put the camera, just where to place the actors, how they ought to move within the frame… there’s nothing incredibly flashy, but it’s unmistakably him. It’s simply a joy to watch.)

Radio On

I think I would have absolutely loved this movie when I was about 17. Which is not me saying I didn’t like it now! In fact, I admire it very much. I just think, knowing me, back then I would have LOVED it.

This is as much of a road movie as I think there can be, in that we spend a lot of time simply looking out the window of a car as we drive from London to Bristol, listening to music. For a bit, I wondered if this is all it was going to be—it was not, it was much more, but it is also that, a lot. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen another movie that names every song (and the associated musicians) we’re going to hear in the film during the opening credits, but then music is so important to this one that it maybe could only happen that way. And Radio On does love music, but this is not a jubilant celebration—the film is quiet, and dark, and bleak, existing in a difficult time in British history, enhanced by the beautiful but minimal black-and-white photography in the movie, the deliberate pace, the lack of emotion from our protagonist, Robert. It’s Britain in the late ‘70s, with its economic struggles, the extreme tension of the Troubles, and the disaffected youth of the post-punk era. Robert is traveling to learn more about the death of his brother, and what we get is a bit of a tour of some of the sadness and sickness of the country, although it’s not all exactly presented so clearly. He picks up a hitchhiker (maybe not by choice) who turns out to be fairly terrifying, but is himself a symptom of the country’s ills. He meets some young German women with their own problems (interestingly, earlier we see some graffiti supporting Astrid Proll, a Baader-Meinhof member), he meets his brother’s girlfriend, who he didn’t even know existed.

But there is always music: Bowie, Kraftwerk, Robert Fripp, Ian Dury, Devo—Robert is a DJ at a radio station and feeds tapes into his car stereo throughout the film. This is the soundtrack to his place in this world. (Sting even shows up as a musician living in a van.) The movie is so evocative of a time, a place, and far more of the feelings of a certain generation forced into that time and place. This is something I very much intend to revisit a few years down the line.

Wednesday, 10/6/21

Returning to Reims (Fragments)

For a while, I did wonder if this was where I was hitting the wall. After 12 days of high-minded, sometimes difficult cinema, it seemed like maybe I just wasn’t going to be able to connect with what I was watching, and that the problem was me, not the movie.

The movie is based on a work by French author and philosopher Didier Eribon, and I wasn’t familiar with the book, so I couldn’t know where this was headed. The first section plays a lot like a memoir of someone describing growing up in a working class family in the 1950s and ‘60s, going back a bit to pick up some of the family history. The approach is certainly novel—Eribon’s story is related in voiceover by a woman, in the first person as if it were her own story, and that’s laid over archival footage of related images: people working in factories, clips from other films, interviews (news interviews? documentary interviews?) with people whose stories are much like the ones we’re hearing. And as an approach to personal storytelling and memoir, this was one I liked, but still, I was having trouble connecting emotionally.

But the filmmaker, Jean-Gabriel Périot (and, I assume, Eribon), doesn’t stay here—or, more accurately, the story opens up into something that makes perfect sense, but that I didn’t expect. We’re taken through Eribon’s family’s political development as working class people, and how that reflects the larger shifts in the French political world, as it relates to the working class. This comes in the form of communism, as they recognize their exploitation, but soon enough also gives rise to nationalism and xenophobia, as immigrants come and also move into the space the working class French are occupying. We see how people are betrayed by the governments they trusted to have their interests in mind, and how that leads them to try more radical movements. We see how these aren’t necessarily “bad” people, at their roots, but how their exploitation and struggle for resources can turn them toward deeply destructive ideologies. And we see how all of this can then give rise to the younger generation’s own reactive and proactive movements, and how and why we are where we are today.

I have, of course, simplified an incredibly complex topic, one that’s expertly laid out through the story of this one person’s family in this film. So much is packed into the movie’s tidy 83 minutes, and yet it all flows as well as any excellently told story. Thank goodness I stuck with this.

Tuesday, 10/5/21

Hit the Road

See, now, this is exactly what I’m always talking about.

This is hardly groundbreaking, but I’m often saying that I regret so much not having all of the context when I watch foreign films, and especially non-Western films, because I always figure I’m missing so much. And in this case, it hurt my perception of the film in the moment, because I felt I’d have two different reactions, depending on if what I was seeing was supposed to be opaque, or if it reflected a definite reality.

And certainly this could have gone either way! For plenty of reasons, but not least because this movie was made by Panah Panahi, who is the son of the famed Iranian director Jafar Panahi, who has long been associated with the late Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami. And “not knowing,” and gradations of reality are par for the course, certainly with Kiarostami, and sometimes with Jafar Panahi, too. (Also, I assume Panah Panahi has more or less had it with constantly being referred to as Jafar’s son, so I won’t do it again after I finish here.) And while there are parts of this movie that remain ambiguous, the main conflict was something that it turns out very much is reflective of reality, but since I didn’t know that for sure, I felt uneasy about how to react.

I’m being squirmy. There’s a reason. The movie opens in media res, with a family of four in their car on the side of a highway, a woman, her husband who has his leg in a cast, their young son, and their older son, who is driving. We don’t know who they are, why they’re there, or where they’re going. They’re trying to wrest the young son’s cell phone away from him so they can hide it in the rocks on the side of the road. Which, yes, seems odd.

We do learn, in drips and drabs, what the purpose of their journey is, but much of the movie is spent with them in this car, and it takes on the tone of a quirky road trip movie—the woman and the older son are nervous about something (someone is saying goodbye?), the father is crotchety but seems to love his family, the young son is hyperactive and precocious. And in this, the movie generally works, it’s pleasantly entertaining, even as we might feel a little worried about what’s to come, and its drawbacks are the same as any other movie of this type (sometimes that kid is just… a little too much). There are some ominous signs that are clear if we have a little idea of life in Iran—the family is certainly worried about being surveilled, or even being followed, which for Panahi is all too real, as his father was convicted of making propaganda and placed on house arrest, barred from making films (he’s found his way around that, thankfully). This much I understood.

But when the real purpose of the family’s journey becomes clear (I won’t divulge it here), this is where I felt unsure. On the one hand, if this was something that does commonly happen in Iran, this gives the entire thing a whole lot of weight I didn’t expect as we began the film. If it was made up, then the movie’s multiple tones were causing me some emotional whiplash that made it feel disjointed and that it wasn’t taking its serious parts very seriously.

To be clear: this is my problem, not the film’s. And, as I said, it turns out that what was being shown is apparently a relatively common situation in Iran, which means the movie’s dark humor works much better, as it’s commenting on and relieving the anxiety of actual difficulties. I learned this later, after reading about the movie when I’d finished watching it, and so I had to put what I’d already seen into this context, instead of having it at the time. And this all extends even further, as I learn even the songs in the film (which are sometimes sung—or lip-synched—by the characters) are also quite meaningful to an Iranian audience. Would knowing this have changed the experience of watching the movie for me? Undoubtedly. Would some of the movie still not quite hit for me? Sure. (That kid is a lot.) This is an obstacle we can usually overcome, and even here we can to some degree, but still, it’s something we need to realize.

By the way, the Iranian countryside is simply beautiful. More Iranian road trip movies, please.

Nature

“You can’t stop what’s coming. It ain’t all waiting on you. That’s vanity.”

I thought of this line from No Country For Old Men while watching Nature, the first feature from Armenian visual artist Artavazd Peleshian in three decades. The entire thing is (supposedly) made of found footage, stitched together in black-and-white montage. We begin with the majesty of mountain ranges and mountaintops, with some breathtaking images (I even wondered if some of them were real at all), but before long those give way to volcanic explosions, then mudslides and tsunamis, and soon enough we see those wreaking holy devastation on cities and towns, with the most enormous apocalyptic scenes you’ve ever witnessed. I do not exaggerate when I say these images are beyond anything I’ve ever imagined—they’re so astoundingly huge, and viscerally real, no zillion dollar CGI spectacle could ever come close to this.

Huge waves crumpling man-made structures that were so large you would have though they’d never move, the water just washing them away like paper. Tornadoes miles wide leveling anything and everything. Lightning crashing down from the heavens. The horror nature can perpetrate is simply indescribable.

And so, here I wondered if we were being told that humans cannot conquer nature, or that here is what we have wrought with our environmental destruction, or that perhaps we are in places we simply shouldn’t be. And all of that is true, and it’s also true that we’ve put ourselves in a position we will not survive, which Peleshian seems to tell us in no uncertain terms. But I think the place I ended up at is that even all of these thoughts are too self-centered. It’s just not about us. It’s vanity to think it is.

Because we also see such cataclysmic images of nature destroying itself. Volcanoes blowing off the sides of mountains, avalanches changing landscapes, underwater fires—nature annihilates, rebuilds, begins again. Worlds change, sometimes so slowly we’ll never see it, sometimes in an instant. For us, humans, we have done things that are making the world uninhabitable (certainly for us, but also for the millions of species we’re killing off, directly or indirectly), but just by way of being here, we are… in the way. Earth will continue to move, continue to change, often terribly violently, and we cannot corral that. We might have thought we could, with our dams, and our bridges, and whatever else we might build, but those are gone in the blink of an eye, in even less than the blink of an eye. It’s as if they were never there.

Monday, 10/4/21

Songs for Drella

Todd Haynes’ documentary on The Velvet Underground is (understandably) the bigger draw at this year’s festival, but they’re also showing this restoration of Lou Reed and John Cale’s concert film, directed by veteran cinematographer Edward Lachman. The two former Velvet Underground members reunited in 1990—musically, at least, there’s every indication that’s as far as their reunification went—to pay tribute to Andy Warhol, who had died just a few earlier, and whom both men had known well. This album is what came of it, along with some live performances, including this one, which Lachman shot without an audience.

The setup is relatively simple as far as concert films go—just Cale and Reed on a stage with their instruments, a large projection screen behind them showing various images, some of Warhol, some of his work, some with more abstract forms. Of course, Lachman (who already had dozens of credits to his name and would go on to work with a ton of exciting and creative directors, Haynes included) knew what he was doing, and he’s very smart about where he puts the camera and when and how he moves it, making this the intimate and emotional performance it had to be, while also keeping it visually arresting and exciting for the viewer. He also doesn’t pretend this isn’t an album, cutting to black between each song and changing the look—sometimes we’re in grainy black and white, sometimes there’s multicolored lighting, sometimes it’s much more stripped-down.

And—as if you need me to tell you this—oh my, those songs. We’re instantly reminded what great storytellers these two are as musicians, and they take us through Warhol’s life (roughly chronologically, as far as I could tell), with some songs using Warhol’s own words, some using their own direct viewpoints, others with more of an omniscient narrator, always with an undercurrent of sadness, and sometimes anger. The pain of their loss is easily felt (and, I think, a lot of other emotions they may have been having unrelated to Warhol), and it’s an experience that gave me a few shivers.

Sambizanga

Another movie restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, this is the 1972 film from French director Sarah Maldoror set in the early days of the Angolan War of Independence (the country wouldn’t achieve independence from Portugal until three years after this movie was made). Maldoror’s husband, Mário Coelho Pinto de Andrade, had, himself, been involved in the liberation movement, and Maldoror based her movie on a novel that tells of Angolan man, Domingos Xavier, who’s kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by the government for being involved in the anti-colonial movement (and, in the movie at least, even more for not giving up the names of others).

The title refers to a neighborhood in the Angolan capital Luanda, and one of the wonderful things about the film is how Maldoror gives us a look at life in the area even while this larger story is going on—something I’ve found that I really treasure about films from this era that come from African countries is that they often aren’t bound by the same narrative structure or arc we’re used to. In this case, we spend much of the movie not with Xavier in prison, but with his wife, Maria, who goes from one prison or bureaucratic office to another trying to find her husband. In placing the focus on her, Maldoror is able to show us multiple layers of the story—we’re able to see the huge role women play in the strength of the community (both through Maria and through a number of the women she meets as she travels), we’re able to see what life in these neighborhoods is like, and we’re able to see the early organization of this liberation movement and how communication happens and these revolutionary bonds start to form. We do, of course, get to Domingos and his murder, which is brutal, but even more than that, we see how his death, and the efforts, small and large, of so many of the Angolan people, help to build this push for independence and to spark a movement that was still very much going on when the film was made.

Sunday, 10/3/21

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?

“Enchanting” is not a word I expect to use when I’m going into a 150-minute Georgian film, but then part of the joy of life is surprise. This may just be my ignorance showing, but my experience with the cinema of former Soviet republics does not include a large amount of whimsy.

Still, here we are, with this charming, curious, playful film from Aleksandre Koberidze, a kind of modern-day fairy tale (or at least it begins that way), and a bit of a fable, too, and a movie that loves the quirks of human beings, and a movie that seems sometimes to encompass all of our lives. Lisa and Giorgi bump into each other by chance and immediately fall in love, and make a date for the following day. But watching them that night is someone with the evil eye. Lisa learns from some inanimate objects (go with it) that this curse will cause her to look like someone completely different when she wakes in the morning—what she doesn’t learn is that the same thing will happen to Giorgi. Each awakes to a new body, and when they go to meet each other the next day, neither recognizes the other. We follow this story for the entire film, but Koberidze delights in the little bits of life, in the stories of all people, in the wind in the grass, in everything that makes this life what it is. He sets his film in Kutaisi, a smallish city on the Rioni River (which is always, always rushing by), and it must be a love letter to that city, too. We take little detours to follow young couples in love, to watch the children playing soccer, to learn about the dogs and their friends. None of it feels silly or cloying, Koberidze seems entirely sincere in his love for the people and the world—he does though, briefly but very seriously, acknowledge this does not represent the whole of it all, as there is so much death, destruction, and devastation we are creating in this world that doesn’t permeate this particular film (something he explicitly says in the movie that he’s wrestling with).

Something I adore when I watch a movie is when it’s quite clear it’s going to do its own thing, when it has a story it wants to tell that may or may not be the story you would have written, and that it’s going to tell that story in the way it sees fit, not in the way you expect or might be used to seeing. “Good for you,” I thought, as I watched this. And the fact that I, in Wichita, can watch a movie set in Kutaisi, and feel like this is me, this is all of us, says something special.

Saturday, 10/2/21

In Front of Your Face

Before this, my experience with Hong Sang-soo was limited to three of his movies, so of the four I’ve now seen, this is certainly the most outwardly emotional. Or maybe the most emotionally serious. Although that depends on what you find emotionally serious? Had you seen these same four films, you might feel differently.

Hong Sang-soo is hard to pin down! But that’s part of his charm, of course. I’m far from the first person to connect him to Éric Rohmer (another astonishing director I’ve only just really come to this year—forgive me, we all find things at our own times), and while no one is or ever will be another Rohmer, this wiggly quality is at least something they share. You begin to try to verbalize just why their movies work so well for you, and you find nothing quite says it.

As if plot were the point, here is a bit of it: a woman returns to South Korea after many years living in the U.S., and is staying with her sister, reuniting with her, in a way. Bits of her life are revealed through conversation, and if we’re paying attention, we can tell something is not quite right. And while what happens is hardly the point, it also wouldn’t be right to reveal it here. As is the case with the other films of his I’ve seen, Hong tends two hold people in a medium or medium long shot and just lets them talk, often about relatively mundane things, and somehow, it’s completely engaging. Nothing with Hong feels forced, which is probably a whole lot of his success—we know people are fascinating just as people, but making space for this to happen is a difficult thing to do, or a difficult thing to do well.

It feels tempting to say Hong Sang-soo would appeal to a particular taste, but I’m not sure that’s true—I think I could show just about anyone this film and they’d be drawn in, there’s just such an ease to his work. The emotional seriousness I mentioned is there, there’s an exploration of mortality and (to a lesser extent) philosophy I haven’t seen from him before (again, I’m no expert), and it gives the movie more weight than I expected. But then, that’s life, you know?

Neptune Frost

I learn this film is an extension of poet and musician Saul Williams’ MartyrLoserKing project, an album that has grown into (or was always intended to be) much more. His focus is the oppressed and their oppressors—there’s not always a definite line between them—and while I don’t know if it’s important to have the context of his larger project in order to understand the details of Neptune Frost, I do know that the larger idea couldn’t be more clear.

Williams wrote the movie and co-directs with the Rwandan actor and playwright (also his wife) Anisia Uzeyman, and they place it solidly in the Afrofuturist tradition, both in style and in theme. This is one of those times when you’ll have to let go of trying to make coherent sense of every piece of dialogue or every scene, because the broad strokes will create the narrative for you, but this isn’t terribly difficult—after 15 or 20 minutes you’ve settled in and it’s fairly easy to go along.

So, having said that, quickly: a ruling party known as The Authority exploits the people in an East African country (I don’t recall it being named, but I believe the movie was mostly made in Rwanda), and some of them have set out for a safe commune where they are amassing to perpetrate a major hacking attack to take down The Authority. Many of them are coltan miners whose labor has kept the government in money and in power, and one of their leaders is Matalusa (Martyr Loser), who connects with our main character, Neptune Frost, an intersex (maybe interdimensional?) being also making their way toward the commune (gender fluidity is also an important concept in the film). Neptune turns out to have the ability to hack into the Motherboard (or maybe Neptune is the Motherboard?), which gives them the opening they need.

I think this is sort of it. I might have misunderstood some of the details. But again, those details aren’t the point, there’s a lot of fuzziness and much is open to interpretation, if you want to interpret it. The larger liberation themes are obvious, and Williams and Uzeyman revel in the science fiction of it all, merging technology with human bodies and creating gorgeous sets and otherworldly outfits.

The film often makes references to a recently past war, which is never described, nor do I think it’s supposed to be assumed to explicitly be the Rwandan genocide, but it did make me think—most of the actors we see in the film are fairly young, which means that time would be barely a vague memory for them (one character describes hiding as a six-year-old with his one-year-old brother), and it made me curious what their experience is like now. Certainly we’re seeing some of that through this film, but I wonder about it in less abstract terms.

At any rate, Neptune Frost also makes plenty of references to all of this being a dream world, or part of multiple dimensions, and drops lines here and there that may help us form our own understanding of what’s happening, not that there’s a single correct interpretation. One line in particular I found helpful for me was this: “The war forced us into other dimensions where the worst already happened. Birds are living witness. They fly through the portals where pain is the only passport.”

Please do not read any of my inability to summarize as dismissiveness—this is a wonderfully creative film (and a musical! Did I mention that?) with important things to say. If you have experience with Afrofuturism, you have some idea of what to expect, it sits very firmly in that world.

Friday, 10/1/21

The Tale of King Crab

A bit of a lull as we gear up for what’s likely to be a busy second week of the festival for me, with just this film over the past two days.

A lull in quantity, but certainly not in quality—The Tale of King Crab is my favorite of the new festival films I’ve seen so far. It’s a movie that steeps itself in that curious dark magic of folk tales, fables, and myths, telling a story made of the fragments of stories passed down through the years. I’ve often said that if I were to change careers entirely, I would study folklore, so, yes, this hits me in just the right spot.

This tale begins with old Italian men sitting around a table, singing songs and regaling each other with tales of times past. These are, apparently, real hunters in a small Italian town who told the filmmakers at least some version of the story we’re about to see, and who begin to tell it again to us: It’s the story of Luciano, a shepherd in a 19th-century village who becomes angry when the prince closes off a path he used to move his sheep. Luciano has somewhat recently returned from Rome, where he’d been receiving treatment for his alcoholism, although it’s clear that treatment didn’t take. He’s filled with anger, which comes barreling out of the frighteningly absorbing eyes of the man who plays him, Gabriele Silli. (Silli has the intense stare of an artist, which, it turns out, he is—this is his first acting role, he works in the visual arts.) He’s also filled with love for Emma (the wonderful Maria Alexandra Lungu, who some may remember from Alice Rohrwacher’s The Wonders), a young woman in the village whose father has no interest in her being with Luciano. But it’s also apparent Luciano is not comfortable with what he feels for Emma, or at least not yet. He’s holding so much back, but whether that’s because of external pressures or his own fear of the storm inside him, we’re not sure.

What we get is what seems to be a bit of a love story, a bit of a portrait of life in 19th-century Italy, a bit of political intrigue (this blocked path is a problem). And then the story takes an extremely sharp (and distressing) turn, and the old men telling the story back in the present day lose the thread. Nothing more is known of Luciano, they say, there are only rumors.

We pick it back up ourselves on the other side of the world, though where, and how, I won’t say, because where it all heads is not something I ever could have expected, into a place where we may have to find meaning in the meaningless in order to have any reason to go on.

From the first shot of the film, the photography is just stunningly beautiful, with the lushness of the Italian village and the movie’s references to Renaissance paintings, and even later when the landscape has changed to something far less comfortable and far more stark—we find beauty in the hideous. Somehow the actors’ bodies seem to meld with the landscape: Emma disappearing into a patch of tall plants, Luciano standing in a lake with the sun exploding off the water causing him to look like he’s the one who’s shining. And then later when he seems to harden into a boulder with so many rocks around him.

This is a story that becomes stitched together from pieces of other tales, from known history, from entire fabrications, and from grand archetypes. In short, it’s how we create our stories, the stories we tell our children and the stories they tell their children. This is a magnificent film.

Tuesday, 9/28/21

The Bloody Child

Just one movie today for me, but as it’s The Bloody Child, that’s plenty. Continuing on with the festival’s lineup of revivals and restorations, this is director Nina Menkes’ 1996 film about the murder of a woman by a Marine on a military base.

The movie opens on a landscape that looks possibly like the American southwest (it turns out to be Joshua Tree), with the barest hint of the morning sun peeking out. We can just make out three figures in the frame, two close together, one farther away, not moving. Eventually, the two figures move toward the third and pull guns, the third drops to his stomach, and we know something very wrong has happened.

The rest is revealed (to the extent it actually is revealed) through an extremely fractured timeline that shows us, eventually, that this third figure is a marine who is driving with a dead woman in his car (very likely his wife), and who is apprehended by military police. And this is more or less the extent of the story. But Menkes tells the story by jumping wildly in time from one point in the day to another, showing us the arrest, cutting to the man driving his car with the body in the back, cutting to a group of Marines standing around waiting after arresting the man, and back, and forth, and forward, and back again. She repeats scenes, sometimes exactly, sometimes by backing up to start them just a few seconds earlier, sometimes having them take place at a different time of day entirely. We rarely see dialogue coming from anyone’s mouth, instead we hear it placed over a scene of people in long shot—it’s often mundane conversation, but she also layers words over themselves, sometimes with two or three people talking at once, sometimes with the same person saying two different things. The approach is not unlike what Steven Soderbergh would do three years later with The Limey, as Menkes evokes the porous nature of memory and our internal dialogues and emotions through her editing.

(A side note: between this and Chameleon Street, I’m starting to wonder if we’re secretly being taken through a program of films that influenced Soderbergh’s work—not that no one else has played with time and memory, but this film bears more than a passing resemblance to The Limey.)

Our “main” character is a Marine officer, a woman, who appears to be in charge of the arrest, played by Menkes’ sister, Tinka. Much of what we see seems to be from her perspective (as much as anything is from one person’s perspective here), and Menkes inserts scenes of this woman at an earlier time, in what are clearly other countries—whether these are memories or emotions isn’t revealed, nor does it matter. Many of them express a sadness that’s hard to put your finger on, most of them simply show people sitting, or lying down, without comment, without explanation. Added to that are the more surreal scenes of a naked woman in a forest and we know Menkes is expressing something less literal and more visceral.

If this all sounds chaotic, I assure you it’s not. This is the first movie I’ve seen from Menkes (a well respected filmmaker who often works in experimental ways), and it was clear from the beginning she was completely in control. The pacing of the film is deliberate despite its shards of narrative, and she expertly expresses internal states without being explicit about what she’s doing—sadness, trauma, confusion, desolation. If this movie is representative of Menkes’ abilities, she’s a masterful filmmaker.

Monday, 9/27/21

Chameleon Street

Hilarious, messy, self-referential, absurd, jittery, literate, crass, disjointed, incisive, transgressive—Chameleon Street is easily one of the most exciting movies to come out of the American independent film movement.

The film won the Grand Jury Prize at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival and then mostly disappeared, and its director/writer/star Wendell B. Harris, Jr., has, to date, never made another movie. The reasons for this have been documented and speculated about in other places, so I won’t do much of that here, except to say that the film is strange and most critics at the time clearly didn’t know what to do with it, and Harris is Black. And in some ways, the film is aggressive about acknowledging his Blackness and the roles Black Americans have to play to get by in a society set up for white dominance.

And oh my, there’s a whole lot going on here. Harris plays William Douglas Street, a real-life con artist who finagled his way into all sorts of places he never should have been, including spending time as an investigative journalist, a surgeon (he performs a hysterectomy in the film after quickly learning about it from a book in the hospital bathroom, an “I can’t believe this is happening” sort of scene), an attorney, and a French foreign exchange student (he does not speak French). He gets his start trying to extort Detroit Tigers leftfielder Willie Horton with nonexistent sex photos, and then when he’s found out he pretends he just wanted to get a tryout with the Tigers. Street is massively intelligent, not just in how he can read people (he says when he meets someone he instantly knows exactly who they want him to be, and that’s what he becomes—hence the title, “Chameleon” Street), but also in his voracious appetite for culture: he quotes the classics, he’s deeply influenced by cinema history (as Harris quite obviously is, too). He plays word games with his speech, even with his insults. He’s also deeply misogynistic, or at least uses misogyny to maintain power over a situation (although, to be fair, if I have to, he uses plenty of unpleasant tools, misogyny just being one of them).

The way Harris does all of this is impossible to explain, it has to be seen, but he mashes styles together, uses wild editing techniques, voiceovers, footage from, and references to, other films, and a thousand other devices to tell this story. I can’t see it as anything but a tragedy that Chameleon Street never really had a chance to find an audience, or that such a smart, wildly creative filmmaker as Harris has never gotten to make another film, but at least now we do have a 4K restoration of the movie, which is what is playing at the festival. Still, despite the movie’s obscurity, it has at least been seen, as its influence can be felt in films ranging from Steven Soderbergh’s 1996 movie Schizopolis to Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You from 2018, and fans of Mos Def and Talib Kweli will delight in an early scene from the film that appears on their Black Star album from 1998. (And maybe there’s more? I wonder about whether any of this was in Spielberg’s mind when he made Catch Me If You Can, and even more if Tony Shalhoub has seen the movie, as the way he asks for a wipe when he plays Adrian Monk is almost exactly the same as how Harris does when he’s performing surgery… a small homage?)

And trust me, stay for the closing credits.

Prism

Back in college, when I learned about how much photography/cinematography was geared toward depicting white skin, and how much of a negative effect that had on showing black skin, I was floored—not so much because I couldn’t believe it, I absolutely could. But more because I’d never even considered it before. It had just never crossed my mind. Yes, a huge part of that is that I am, myself, white, but as the documentary Prism shows us, this is something that’s ingrained so deeply in the entire art form that even the technology is set up in a way that bends us in that direction. Cameras and lenses are calibrated for white skin. Film stock, too. The way we learn lighting. All of it. As the movie points out, much of this is less a conscious effort to exclude skin that isn’t white, and more the fact that we treat white skin as the default, as “skin.” Think of how Crayola eventually had to change their “flesh”-colored crayon.

While this realization is not, now, new to me, the way Prism handles it is not what I expected—the film is made by a white Belgian woman, An van. Dienderen, though she smartly stays mostly out of the way and brings on board two Black filmmakers to co-direct, the Cameroonian director Rosine Mbakam, and Éléonore Yaméogo from Burkina Faso. And rather than simply state that the problem exists, as if that would be enough, the women interrogate the problem through history, philosophy, film theory, technology, and personal stories, including indicting themselves for being complicit in perpetuating this structure and passing it on, something that’s particularly eye-opening to hear from the Black women in the film. They examine what it means to impose one’s worldview onto another, to force them to look a certain way on film, or even to exist in the frame at all, a sort of artistic colonization. And certainly they investigate the erasure of the beauty of non-white skin, as the wide range of colors and subtlety is flattened into murky monotone in so many films and photographs.

Is all of this too wide-ranging for a 78-minute film? Probably, as it sometimes feels unfocused (I haven’t even mentioned everything they cover here). It does all circle around the same theme and topic, so none of it feels irrelevant, but I suppose this is my way of saying the movie could have been longer in order to explore some of these ideas more deeply. As it eventually says, this is not necessarily a problem without a solution, and we can see plenty of examples of filmmakers who have learned how to work with the technology to express non-white skin with the vibrance it truly has (I think immediately of the work Barry Jenkins has done with cinematographer James Laxton). The film point out, rightly, that at least now we realize the problem exists, and we can take real steps to change things.

Sunday, 9/26/21

Kummatty

Another of the festival’s revivals, and this one’s a biggie. Kummatty is the 1979 movie by Indian master Govindan Aravindan, and it’s been restored by Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation and their World Cinema Project (responsible for reintroducing a number of important films from world cinema history to wider audiences). Me, I’m a sucker for anything related to folklore, and this movie draws on stories from the Indian region of Malabar about a mysterious figure who reappears time and again in a village, drawing the attention of all the children, who sing songs and tell stories about him. He’s seen to be a magical figure, although it’s not clear for some time whether or not he actually is.

Even more than just relating folklore, though, this movie bathes us in what life in this Indian village must be like, in some ways almost existing outside of time—it spends a lot of time on the landscape (some of the shots, especially in the introduction, made my eyes pop wide open, they’re so stunning), with the children and their songs and poems, with the people gathering water. Some of the songs the children sing about Kummatty make us think he might be a sinister figure, though certainly they’re all attracted to him (not that this tells us anything, as we’ve learned from the Pied Piper), and the older people in the village don’t do anything to try to run him off. We do find, after quite some time, that he does, indeed have magical powers, and he turns the children into animals, which results in what seemed (to me) to be a hard left turn into a harrowing section of the movie in which I wasn’t sure if one of the children was going to be ok.

This is exactly one of those movies where I know I can enjoy it on my mostly ignorant level, but I deeply wish I understood the cultural context that would fill in many of the holes for me, as I’m certain I’m missing so much. But for those of us in public radio, one of our greatest values is the pursuit of lifelong learning, and this is just the sort of thing that makes me search out more, to learn what I can outside of what I’m presented here. Which means Kummatty is the kind of movie I treasure the most.

El Gran Movimiento

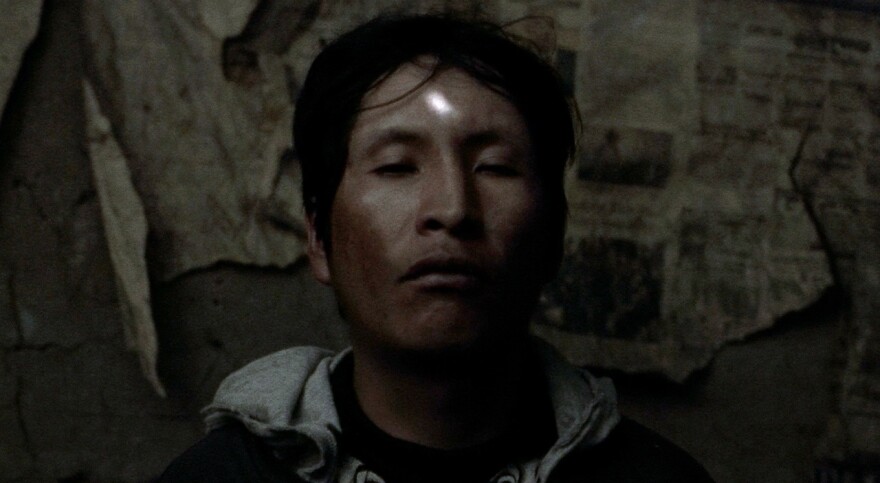

A bird’s-eye view of La Paz shows us just how packed the Bolivian capital is. Buildings so crammed together you can’t tell where one ends and another begins, as if they’re sprouting out of each other, one on top of another on top of another, like the layers and layers of flyers plastered over each other on city walls.

Miners have come to the city from less urban areas looking for work, any work, as their prospects elsewhere have dried up. We spend the movie with three of them as they navigate the city, and as one of them, Elder, develops a mysterious illness. He says it’s the altitude, the doctors say it’s stress, someone else wonders if it’s a demon (“we don’t believe in that anymore,” says a doctor). Elder meets a woman who claims to be his godmother, Mama Pancha. He says he doesn’t remember her. She helps them find work and connects Elder with Max, a man who lives outside of the normal societal structure (in his behavior, yes, but also we first meet him in the woods, and he’s the one character who seems to spend most of his time outside the city). Max may have the ability to cure Elder’s mysterious disease through his own mysterious means.

El Gran Movimiento is the kind of movie that will frustrate many people and captivate others—I tend to have a high tolerance for ambiguity, so I lean toward the latter, but I understand either side. I’m certain I completely missed some cultural context, but I also think plenty of what we see doesn’t have an explanation, or isn’t so much supposed to make literal sense as it is emotional sense. The story is elliptical, at least one scene happens twice from two different perspectives (although you’ll have to be paying attention to see it), and there are times you either have to go with what’s happening or not, particularly when a dance sequence breaks out, a wild tone shift from the rest of the film (me, I went with it). The director, Kiro Russo, does an incredible job playing with sound and light—there’s one scene with the miners in a cable car, when Elder’s sickness is becoming clear, where the light and shadows themselves appear to infect him.

Sickness as a metaphor for the ills of technological progress/urbanization/colonization/etc. is nothing new, although it does hit a little differently right now while we’re living through this pandemic. But that doesn’t mean it’s not effective, as there’s something about our fear of disease that makes us feel it in our guts. But by the end, when Elder has been cleansed, his strong, clear breath is massively refreshing.

Saturday, 9/25/21

Social Hygiene

About three minutes in, I thought to myself, “Oh, wow, the entire thing is going to be like this, isn’t it? Am I going to be able to do this?”

To answer those now: Yes and yes. And to take it further, I actually had a pretty good time.

What the “thing” is “like” is this: A woman in white and a man in black stand in a field, about 20 feet away from each other. The woman stands arms akimbo and never moves, or never moves until one exasperated gesture at the end of this 13-minute take. The man never moves from his spot, though he’s much more demonstrative, and we quickly learn he’s not quite as bound by convention as other people might be. We see the two in a static long shot through a smudged camera lens, and they speak to each other very deliberately, with two-second silences between each person’s next line of dialogue, the woman almost shouting.

And this really is how the entire movie is, made up of six or seven scenes just like this, each with the same man, named Antonin, talking to a different woman (though they repeat later in the film), with each woman frustrated by Antonin and his way of life. He’s a bit of a rogue, a con man, he’s broke, he’s in love with a woman other than his wife, and he delights a bit in the frustration he causes. That woman in white is his sister, Solveig, who wants Antonin to get his act together, and through the course of the film we meet his wife, his paramour, and a tax collector, among a few others, each in long shot, each standing in place, each at a distance, each trying to get Antonin to shape up in one way or another.

And here I’ve spent all this time with a description that would not at all entice me to watch what turned out to be a reasonably entertaining, certainly clever, curiously engaging movie. Now, it is all of those other things I said, and to be fair, I really don’t think director Denis Côté has any interest in enticing anyone to anything. But this isn’t just a formal exercise, it’s also slyly funny in a way I never expected when it began, and at 75 minutes it’s short enough you can bear with the style if that’s something that would normally grate on you. Now, of course Côté knows what he’s doing with this, and he knows how a lot of people might react to such an aggressively strange approach, and he plays with that to surprise us with unexpected humor, light wordplay, and a few sight gags that gave me a big smile, if not actual belly laughs.

Côté claims this movie was conceived well before the pandemic, but whether that’s true or not, art takes on the context of its time, and watching these characters keep such a physical distance from each other is striking when we know the movie was also shot under conditions that necessitated exactly what we’re seeing. Sometimes things work better because of circumstances that are out of our control, and I think I had more patience with this than I would have were we not living in this particular time in our history. But we are, and I’m glad I had that patience, because I will think of Social Hygiene a lot more fondly than I might have otherwise.

Hester Street

Carol Kane has played so many overwhelmingly nutty characters that it’s easy to forget (or never to have known) it wasn’t always that way for her. Not that I’m upset she plays those characters! She’s a treasure. But it’s truly lovely to see her in a role like this one, a role that got her an Oscar nomination, as Gitl in Joan Micklin Silver’s gently funny, quietly sad portrait of late-19th-century Jewish immigrant life in New York City. The movie is part of the festival’s Revivals section, made in 1975 and having recently been restored from the original negative, and despite its extremely low budget ($370,000, apparently), it looks gorgeous and feels authentic, and it’s able to thread that needle of telling a story so specific to its characters, but that also feels universal.

It takes a bit for Kane to show up, as we start the movie with Jake, who’s come to America recently enough to still be excited by it, but long enough ago that he’s settled into the rhythms of New York life. He’s met some women, he’s got a job, he has an apartment. He also has, it turns out, a wife and child, whom he receives at Ellis Island, and we see how much that old life no longer suits him. His wife, played by Kane, understandably struggles to instantly adapt to American life—she doesn’t speak the language, she’s not used to the more freewheeling (and less religious) social expectations around her, and this frustrates Jake to the point that he more or less gives up wanting anything to do with her.

Kane never has a huge blowup or anything that signals a Great performance, but we see her heart break in all sorts of little ways, as she’s confused by this new life and by the husband who no longer seems to exist. As it becomes more and more clear to her that the life she thought she had is gone, or is slipping away beyond her control, we ache for her. But we also feel a tiny bit of happiness, because it becomes clear she has other options, even if they weren’t the options she thought she had.

This is the story of so many lives, of how people change and we can’t really fight it, of how doors open and close, of how these kinds of stories are always going on, amid the bustle of a new world and a busy city. And it’s the story of a woman trying to get by in a man’s world—not even trying to blaze a trail, just trying to live a modest life under conditions that simply take for granted that she’s not as important as her husband (we learn at one point that upon divorce, she must wait 91 days to remarry, while Jake could remarry the second he walks out the door).

Anyone familiar with Joan Micklin Silver will not be surprised to hear this is an excellent film, but even so I was struck by the generosity she shows toward Gitl and how she doesn’t do anything showy to pull at our heart strings, telling the story is enough. The film’s black-and-white photography looks fantastic and helps its small budget along to place us in a fascinating time in our country’s history. And Silver drops in little scenes here and there that essentially play like short silent movies, which also helps us fall back into the past (anachronistically or not). This is a really, really nice movie.