Kathleen Holt reminisces about her final moment inside the original High Plains Public Radio studios.

It was a former schoolhouse in tiny Pierceville, 16 miles south and east of Garden City. She remembers the bare nature of that first studio; desks were made from donated concrete blocks and discarded doors.

It was the late 1980s, and she had just helped her colleagues move to the new studios in Garden City. Holt and a team of volunteers had raised $600,000 at the time to purchase and renovate a historic building near downtown. They fielded proposals from several different communities in southwest Kansas and eastern Colorado, but chose Garden City for its central location within the High Plains region.

Holt says the on-air announcers were broadcasting from the Garden City building for a month while the old audio control board, and a board operator, remained in Pierceville. The day after they moved out of the Pierceville building, she remembers going back to pick up some mops and buckets that were stashed next to the audio board.

“I was the last person to go in the Pierceville studio after it was closed,” she says. “It was all empty and just sad, sad, sad.”

Holt was shocked when, upon her return to the studio, she found the roof had collapsed, destroying the audio board and her cleaning supplies.

“If we had not moved out before that day, and the ceiling gave up, somebody would’ve been under it for sure,” she says. “I always think about that.”

Today High Plains Public Radio staffers aren’t worried about the ceiling literally falling in, but it has, metaphorically, after $1.1 billion in federal funding was rescinded from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting this summer. The action means the CPB will shutter in January. The same bill also rescinded $8 billion from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Sen. Jerry Moran’s statement on the Rescissions Act of 2025 has no mention of public media. In an email, Moran wrote that Congress rescinded funding for the CPB to save taxpayer dollars and because of its national leadership’s departure from its non-partisan mandate. Moran wrote that he will continue working to prioritize the needs of rural Kansans and look for ways to provide resources to local broadcasting.

For High Plains Public Radio, it means a loss of $550,000 over the next two years, or about 15% of the station’s budget. Holt and other longtime station employees are stressed by the thought of having to fill that gap with donations. However, they are also buzzing after receiving a three-year, $750,000 grant from Press Forward, a national philanthropic coalition investing in community journalism and civic equity.

The station received news of their grant award one day after federal cuts were enacted in June. The grant will be used to establish a regional news and information network – something Holt says will benefit and unite residents of the vast, mostly rural High Plains region.

“I’ve gotten the chills when I’m driving across I-70 listening (to HPPR),” she says, “and I just think, ‘We did this. The people from here did it.’”

VISIONARY LEADERSHIP

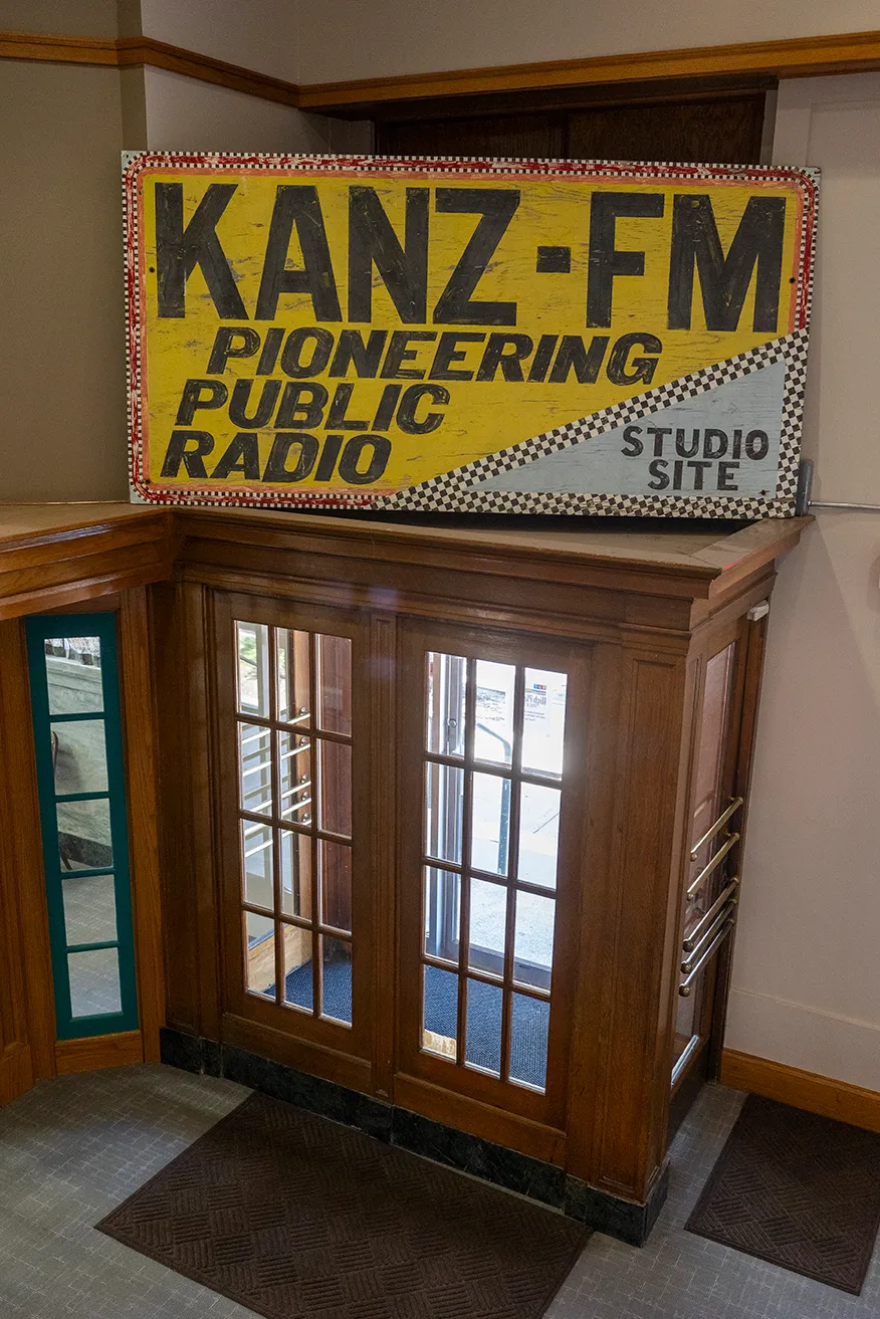

The Garden City studio of KANZ-FM, is full of well-preserved artifacts collected since the station’s establishment in 1977 and awards received for both broadcasting quality and community involvement.

A second studio is now operating in Amarillo, Texas, to reach more people across the southern High Plains. In total, High Plains Public Radio has 19 FM-band stations and translators, covering 78 counties across western Kansas, eastern Colorado, southwestern Nebraska and the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas.

Garden City native Quentin Hope is the executive director and the station founder. Holt, who has assisted Hope with growing the station since 1977, calls him a visionary for his creative ideas and continued leadership. She says Hope believed in the power of public radio to serve the High Plains before anyone else.

“The Corporation for Public Broadcasting funded a consultant to come out here from Chicago,” she says. “At the time (in the late 1970s), the only rural stations were licensed to Native American tribes and school districts, but there were no community licensees to rural areas.”

According to Holt, the CPB required a population of at least 300,000 people to sustain a 100,000-watt public radio station, when the total population of southwest Kansas at the time was about 65,000. That didn’t deter Hope, Holt or the station board of directors, who voted to proceed with the formation of the station anyway through a grassroots fundraising effort led by Holt and her husband at the time.

“That was a turning point at which we began to think, ‘Maybe we can do the impossible,’” Holt says. “It truly was a new way of looking at things, and we did it with a fifth of the population that we were told we needed.”

‘GHOSTING OF NEWS’

Hope’s work to grow the civic presence of High Plains Public Radio is his bread and butter, so to speak, for which he doesn’t receive a paycheck. His paid work comes from media consulting and as co-lead of the Poynter Institute’s digital transformation program, where his main directive is to build online audiences for small publications.

Hope had no clue that public radio and TV existed at all until he went to Oberlin College in Ohio.

“It was primarily an urban thing at the time,” he says. “If you were growing up in Garden City in the 1970s you wouldn’t know that such a thing existed.”

After he finished his undergraduate degree, Hope returned to southwest Kansas with the idea that public radio “made sense everywhere,” especially on the High Plains where FM signals are still few and far between.

As an added benefit, the cost of production was lower for public radio than TV, and Hope says that allowed local residents to get involved on a part-time or volunteer basis with the development of the station, which in turn kept the shoestring budget tight and also provided a space to grow a virtual community before the existence of the internet.

“Part of it was, we billed it as ‘an ear to the world’ by providing good national and international news and arts programming through our partners with NPR and BBC,” Hope says. “We also talked about being the voice of the High Plains, and being able to build a community of interest.”

Hope grew up with direct ties to the region’s history. His mother, Dolores Hope, worked as a columnist, reporter and editor for the Garden City Telegram from 1954 to 1998. Writers Truman Capote and Harper Lee were guests of the family when they visited southwest Kansas to document the 1959 Clutter family murder case. Hope’s late father, Clifford, was a longtime attorney in Garden City who represented the Clutter estate.

Dolores Hope served on boards for the Garden City school district, the local YMCA and church groups throughout the 1970s and 80s. Even after retirement, she wrote columns for the Telegram reflecting on local life, and volunteered her time in the community. She died in 2014 at age 89.

Hope, who is one of six children, attributes his passion for journalism to his mother. He recalls a boyhood errand of running his mother’s articles to the newspaper office a few blocks from his home.

“At that time it was a busy newsroom,” he says. “I can remember the smell of the Linotypes going into the managing editor’s office. The Telegram was always a big part of our lives.”

Hope says the media landscape has changed dramatically since his mother received her journalism degree from the University of Kansas in 1946.

The Garden City Telegram, for example, was owned and printed by Harris Enterprises of Hutchinson from 1953 until 2016. The newspaper is now owned by New Jersey-based CherryRoad Media.

Hope says what was once a bustling newsroom at the Telegram is now a municipal courtroom and only two full-time employees remain on staff. It’s an example of what he calls the “ghosting” of news, where the presence of local media is thinned through corporate homologation to the point of eroded community trust.

“I think it’s unfortunate from a community’s point of view,” he says. “They either feel they’re not thought of, or they’re isolated in general.”

Public media outlets around the state and country are feeling the impacts of rescissions. Smoky Hills PBS general manager Betsy Schwein wrote in an email that federal funding cuts eliminated almost 52% of the TV station’s overall fiscal year budget. Halved funding means some adjustments will be made to the station’s programming, such as ending Lawrence Welk reruns, but Schwein wrote that viewers will likely not see any difference in content overall.

The 10 full-time station employees, who are spread between Garden City and Amarillo, aren’t currently at risk of being laid off. Hope is actually seeking to expand staff to accommodate his vision for the new Civic Media Network.

CREATING A NETWORK

Hope’s daily schedule is stacked with Zoom calls and correspondence about the formation of this new contributor-based platform for news and community information.

His current barrier to building the Civic Media Network is the actual networking needed to create a pool of regional contributors. Hope’s plans include assembling a group of up to 50 contributors to curate and submit news stories from as many of the 89 counties and 332 communities in the station’s listening area as possible.

He’s also formulating at least two full-time job roles attached to the Civic Media Network, likely an overall program manager to gauge interest across the 300-plus communities and an editor to check submitted stories. More information on any new positions should be available this fall.

Hope’s goal is to form connections throughout the High Plains to provide better news coverage and help span political and social divisions present throughout the vast region.

For Holt, she’s noticing more blatant divisiveness in her community of Cimarron, an agricultural town of about 1,900 people 34 miles southeast of Garden City. She is hopeful the Civic Media Network will encourage rural residents to participate in their communities by emphasizing local information, and more importantly to her, that it will promote voices of High Plains denizens in a thoughtful and intelligent way.

“One of the most offensive terms I’ve ever heard used to describe this area is ‘brain drain,’” Holt says. “What about my brain? It implies that everyone who’s still here is stupid for staying.”

Holt owns and operates the Historic Cimarron Hotel and coordinates the HPPR Radio Readers Book Club, where listeners can submit short book reviews. Part of her experience as a radio station founder is the revolving door of employees who, for one reason or another, she says, didn’t enjoy living on the High Plains. She wants to see the network consist of local leaders who show care for their communities and the greater region.

An example of the contributor network Hope is attempting to achieve is the Wichita Documenters program. Launched in May 2024 under the national Documenters organization based in Chicago, it’s funded by the Wichita Foundation and managed by the Kansas Leadership Center, publisher of The Journal, and other partners within the Wichita Journalism Collaborative.

Community members are trained and compensated for attending public meetings and taking detailed notes that are available on the Documenters website. Manager of the Wichita program, Debbie Haslam, says about 40 people throughout the community are active note-takers, and some of their notes have resulted in news coverage. An increased number of note-takers in a town, or indeed several towns across a region, can heighten awareness of local issues, Haslam says.

“You’ll get stories that maybe matter a lot to your community but that people weren’t aware of,” she says. “It makes them more aware of how things affect them, no matter if it’s a town of 500 people or 500,000.”

BIG PLANS

The grant Hope received from the Civic Media Network covers both the effort required to coordinate the network as well as research to determine what audiences want from their local media. Annual fundraising is also underway at the station through on-air pledge drives.

Hope and his team want to raise half a million dollars over the next two years to bridge both the metaphorical gap between political leanings and the literal gap left by the elimination of the CPB. On raising funds, the station is already almost halfway to its mark. By September 30, the station had gathered $250,000.

Hope views the new network also as a tool to help rebuild overall trust in news.

“Radio has always been very good for that because it can be more personal,” Hope says. “It’s a real person’s voice that you’re hearing.”

A native of southwest Kansas, AJ Dome has a background in radio news, TV production and newspaper reporting. He has reported as a correspondent for The Journal since 2023 and is based in Garden City.

This article was provided through the Wichita Journalism Collaborative, a partnership of 10 media and community partners, including KMUW.