Natalie and Alex Beauchamp have moved five times in the past four years.

They’ve fit their lives into apartments across Missouri and the Kansas City area. It’s only recently, when Alex Beauchamp’s promotion required a move to Wichita, that the 20-somethings thought to try their luck at buying a home.

City leaders talk a lot about attracting people like the Beauchamps to Wichita: young professionals ready to establish roots. But planting here is harder now than 20 years ago. Especially for first-time buyers.

The Beauchamps did just about everything right, according to their real estate agent, Jayna Reece. They arranged their financing, tempered their expectations and became eager students of her guidance about the home-buying process and the Wichita market.

Even so, they had a six-week whirlwind of house searching.

The Beauchamps sought a $225,000 home with two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a one-car garage and in a desirable location. Enough room for them, their four cats and occasional guests.

It’s the kind of home that made up the core of Wichita housing stock for decades.

Today, entry-level homes are a hot commodity. That’s because the city is still weathering the effects of a bust in residential construction that began with the 2008 Great Recession and continues to this day.

To understand the full impact of that slump, the Wichita Journalism Collaborative – a coalition of 10 organizations that includes KMUW and The Journal – reviewed 20 years of building permit data from the Metropolitan Area Building and Construction Department, the consolidated city-county agency overseeing construction in Wichita and much of Sedgwick County.

A WJC analysis of the records shows a long-term decline in building that has compounded over time. Wichita is missing 17,000 single-family homes that would have been built if the community had kept building at its pre-recession pace. At the current clip, it would take more than 25 years to catch up.

But Wichita needs a lot more homes – now. The city’s current housing shortage sits somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 units, officials report, a number that could surely grow.

The data also showed how the recession thinned the ranks of homebuilders operating within Wichita. The number of builders issued permits to build housing dropped from 199 to 134 between 2005 and 2023. Only 18 applicants from 2005 secured permits for the same purpose in 2023, a window into how the downturn hollowed out the industry.

The result is that buyers like the Beauchamps count themselves lucky to find a home in their price range after six weeks of searching.

While still living in Shawnee, Kansas, the couple arranged six house showings. Properties they loved got snatched up in bidding wars. Friends offered the Beauchamps first dibs on their home but then backed out once they realized its value on the open market.

“We would find a place that we maybe wanted to look at or that we thought we were interested in and then, ‘Boom.’ Next day, it’s pending,” Natalie Beauchamp said. “Some things just go super quick, especially in our price range, and for things that are good to go.”

Real estate agents say the Beauchamps were looking in a difficult section of the market — move-in ready homes that fall in the $200,000 to $250,000 range. There’s competition not only from other first-time buyers, but also from investors looking to flip a property for a decent return.

“If you love it and think it’s nice and beautiful and wonderful,” said Reece, the real estate agent,” so do the other buyers who have seen probably the same other houses that you have.”

The dearth of residential construction affects more than just first-time homebuyers. It drives everything from rising home prices and soaring rents to escalating valuations and the higher property taxes they bring. It keeps empty nesters from downsizing and that, in turn, blocks younger families from buying in desirable neighborhoods.

There’s an obvious solution – build more housing. A lot more.

But that’s tough to do quickly.

“If you walk three miles into the woods, turning around is the first step,” said Stanley Longhofer, a professor and director of Wichita State University’s Center for Real Estate, in an attempt to put the scale of the challenge in perspective. “But you still have to walk three miles to get back out of the woods.

“These problems that have been building up here for 15, working on 20 years, you can’t expect them to be solved overnight.”

How We Got Here

In nine of the past 18 years, the rate of housing growth has trailed the rate of population growth in Sedgwick County, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, although only just slightly for the entire period.

Ensuring that a community’s housing supply is keeping up with its population growth is really important for “making sure economic growth benefits all residents,” said Kathleen Bolter of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a nonprofit, nonpartisan independent research organization based in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

The institute’s research shows that even the building of luxury housing can be helpful if it decreases competition among wealthy families and other buyers. But market-based solutions have limits, too, she said, and must be mixed with nonmarket solutions, such as tenant protections and direct public assistance.

Kirk McClure, professor emeritus of public affairs and administration at the University of Kansas, contends Wichita could miss the mark if it doesn’t view the shortage of affordable housing as a challenge with income rather than a lack of supply.

“I have often argued that the best affordable housing program is to raise the minimum wage to a true living wage,” McClure said. “A minimum wage of $20 to $24 per hour would solve most of the housing affordability problems.”

To hear Wess Galyon tell it, Wichita has never been a high-volume market. Galyon is the president emeritus of the Wichita Area Builders Association. He spent more than three decades as the head of the regional builders’ group before its new president and CEO, Tyler York, took over earlier this year.

The nature of Wichita building, Galyon said, is focused on an array of builders providing quality homes for each individual buyer. That’s in contrast to other markets where a handful of builders dominate, churning out hundreds of homes each year.

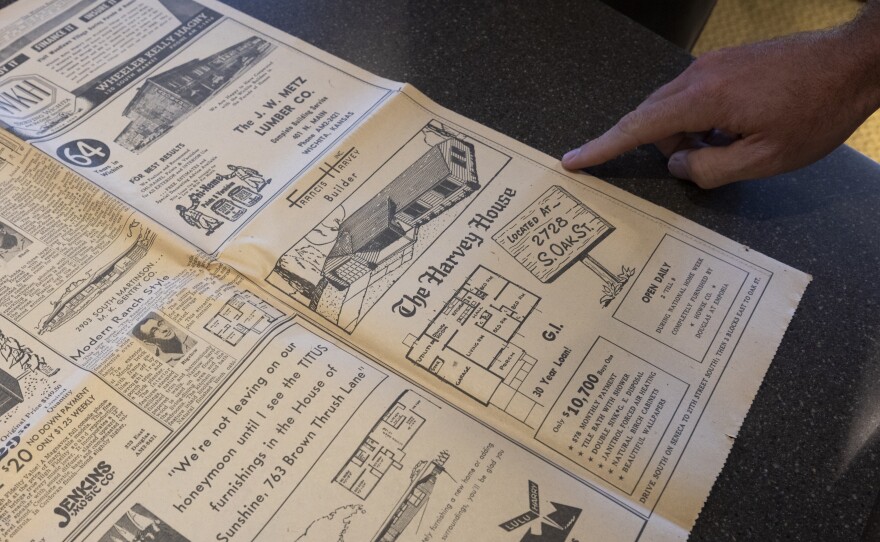

In the early 2000s, long-standing family home builders anchored the builders association. Many were first- or second-generation firms that started small and worked to build a legacy to pass on to their children.

Craig Sharp, of Sharp Homes, was one. His father, Walter, founded the company in 1965 in Augusta while teaching at the Wichita Area Vocational-Technical College. Sharp joined the business after college and took over in 1992.

In those days, the company’s business was almost exclusively starter homes, which it scattered across Bel Aire, Andover and other nearby areas.

Between 2005 and 2007, Sharp said business was booming. He said the majority of the business in the market was in constructing entry-level homes and move-up homes.

“I was right in the middle of it, and we were busier than we ever were,” Sharp said. “We were building more units than we’ve ever built – even to this day. … The (interest) rates were reasonable. Economy was good. It was just a busy time.”

The recession stopped that trend, Galyon said, when people lost their jobs, saw their credit ratings take a hit and began shying away from greater debt loads.

“It takes time for that to cycle. For us, we’re at about a 10-year cycle when the bubble bursts,” Galyon said, referring to the rebound period for building more housing. “Economists say, ‘Well it will be 18-24 months.’ Well, nine, 10, 11 years later, and we’re still recovering.”

Consumer hesitancy turned a predictable field unstable. Jay Russell, one of Wichita’s most prominent developers, said the construction community suffered a corresponding dwindling, with metro area builders shrinking from about 100 to roughly half that amount today.‘

Turning to niches

With the workforce shedding contractors and tradespeople, builders weathered the downturn by pivoting away from Wichita’s successful model: building entry-level homes.

Scott Lehner, the co-owner and chief executive of Perfection Builders, said his company “looked like just about any other builder” in Wichita prior to the recession. He and business partner Jason Ronk started Perfection Builders in the early 2000s, building typical three-bedroom, two-bath ranches with a basement.

“Everyone was kind of building the same stuff and trying to put it in a different color wrapper,” Lehner said.

The recession brought transformation. Lehner and Ronk decided to franchise with Epcon Communities, an Ohio-based company that develops age 55-plus communities.

Perfection Builders carved out a new niche: zero-entry and slab houses. The two models pair together well. Zero-entry homes are designed without stairs, allowing people of all mobility levels ease of access, while slab homes ditch the basement and build off a flat concrete pad. The end result is a cheaper, quicker build that works for a generally older clientele who are looking for a second home or a home to age into.

“People were ready for them,” Russell said.

Sharp Homes also moved away from entry-level models. The shift to custom designs was natural, considering Sharp’s love of architecture, and it attracted a wealthier clientele less worried about mortgages, interest rates and rising costs.

Today, Sharp Homes typically builds in the $600,000 and above range. In 2024, it became the biggest builder in Wichita, constructing 145 homes valued at about $68 million, according to the Wichita Business Journal.

Perfection Builders, placed second in the ranking, with 122 homes valued at $43 million.

Building slowly picked back up around 2013. In the market that remained, fewer builders were working with fewer contractors to build more expensive homes. By the time the pandemic hit, single-family home building activity had climbed to about a third of its peak in 2004.

Even through the pandemic, Wichita builders stayed busy. But a demand for more single-family housing – and larger housing properties – collided with materials shortages and declines in the homebuilding workforce.

Tony Zimbelman spent most of his 30-year-plus career working on affordable housing projects. During the pandemic, he worked on the largest home of his career: an 8,000 square-foot mansion.

It took six months just to install the heating and air conditioning systems. Money couldn’t speed up the process because there weren’t enough skilled laborers to hire.

“A lot of builders just got fed up with that, and more of them retired than what I thought would have,” he said.

The net result now is a local industry with fewer builders, fewer tradespeople and more companies focused on niches and custom-designs, rather than the entry-level single-family market.

In short: a broken system for choice and affordability.

“If you walk three miles into the woods, turning around is the first step. But you still have to walk three miles to get back out of the woods.”Stanley Longhofer, a professor and director of Wichita State University’s Center for Real Estate

Building in a changing Wichita

The solution, according to Longhofer, the Wichita State professor, is to make it easier to build homes in Wichita. That would have to take place on an extended timeline – five to 10 years. But the issues that have to be addressed are thornier than just streamlining permitting or zoning processes.

To go big on building, Wichita needs more workers – plumbers, electricians, drywall installers, framers, etc. Some efforts are already underway to bring this about.

Wichita Area Builders Association President Tyler York said his organization partnered with Butler Community College last year to begin a Build My Futureprogram. An event in March to build connections and explain options drew more than 1,300 young people. Another is planned for October.

But don’t expect an overnight change.

WSU Tech works closely with groups like Associated General Contractors of Kansas and its Build Up Kansas initiative, providing a curriculum and connecting students with industry opportunities. It also partners with companies like Trane to grow the number of qualified HVAC technicians entering the workforce, spokeswoman Mandy Fouse said.

WSU Tech is experiencing strong growth in its construction-related programs, but interest in core construction science and carpentry hasn’t been as strong, Fouse said. Skilled trades areas, such as climate and energy control, see high demand, and an electrical technology program launching this fall quickly filled up.

“The long-term trend in skilled trades has been positive, especially where there’s a clear link between training and good-paying, high-demand jobs,” Fouse said.

Even if Wichita were to have the plumbers, electricians, drywall installers and framers it needs, the Wichita they’d be constructing would look different from the past. While single-family homes remain a mainstay, Wichita also needs duplexes – what Longhofer prefers to call “twin homes” – and multifamily residences.

That new look is already on display, having taken shape over the past decade, based on a Wichita Journalism Collaborative analysis of building permits filed with the Metropolitan Area Building and Construction Department. The consolidated city-county agency is responsible for making sure structures meet regulations and safety standards.

Back in 2004, more than nine out of every 10 housing building permits closed – meaning the structure is finished and certified for occupancy – were for single-family homes. In recent years, single-family homes have accounted for only 60% to 70% of new construction.

Duplexes have been proliferating though, reaching a high of 361 closed permits in 2023. (Single-family homes accounted for just 585 closed-permits that year, the closest spread between the two over the past 20 years.) But they might not do much for home ownership because duplexes are rented out more often than they are bought.

Yet their growing presence signifies the possibility of a new era, if Wichita embraces a diverse housing future where the single-family home is one choice among several.

“Wichita has always been a single-family neighborhood (community),” Russell said. “But it’s starting to become a duplex city.”

But there are downsides.

Russell has built his share of duplexes, but he said he’s ditching that model because “they’re saturating the market.” Reports of Wichita’s housing shortages have caused a “euphoria with out of town investors” who he claims are moving into Wichita from markets like Dallas.

These investors – along with local builders – are building dozens of duplexes that aren’t doing much for homeownership rates but are creating cheaper and cheaper rental properties.

Russell stopped building duplexes because he couldn’t profit from units being rented for $1,600 to $1,700 a month. Today, he says, duplex rents are trending several hundred dollars cheaper.

“I would just hate it if 50% of the housing product that’s built in the next several years is duplexes,” Russell said. “We need to get back to more single-family home ownership, pride of ownership.”

Russell’s alternative is designing and building more “splits” – duplex-sized properties split apart at their adjoining wall and divided by about five feet of space. Russell said that these models could help fill the entry-level market, selling for between $205,000 to $220,000 for a three- or four-bedroom model.

But observers said not everyone loves the concept.

“When you think of Wichita, there is still a good portion of our population that feels that the best way to improve Wichita … is to restore it to 1950s museum quality. And I get that,” said Chris Labrum, the director of the building and construction department.

Those yearnings may not include duplexes showing up near homeowners’ cul-de-sacs. While some neighbors can be satisfied if the buildings meet certain aesthetic parameters, others oppose them fundamentally.

“You’ll have a segment that’ll go, ‘That’s all I’m asking for,’” Labrum said of cosmetic adjustments. “And then you’ll have a segment that says, ‘Do you know what kind of people live in duplexes? We don’t want those people in our neighborhood. We don’t want landlords. We don’t want rentals.’”

“It’s surreal. Like when you walk outside and look around at a beautiful sunset.”Alex Beauchamp, first-time homebuyer

Is the issue building or affordability?

The idea that communities can build their way of a housing crisis isn’t unique to Wichita.

Two authors, Derek Thompson of The Atlantic and Ezra Klein of The New York Times, published a book this spring called “Abundance,” which makes a case for progressives to adopt a pro-building attitude on issues such as affordable housing to address what they see as the failures of liberal governance. The New York Times Magazine recently touted the benefits of sprawl.

But McClure, the KU professor emeritus, is among those who have found the opposite.

In a study published last year with Alex Schwartz of The New School in the journal Housing Policy Debate, they argued that most communities in the United States have ample housing. What they lack is enough units that very low-income households can afford.

McClure and his co-author contend that helping renters and moderate-income buyers better afford existing homes would be more cost-effective than expanding new home construction in hopes that an expanded supply would bring prices down.

“Our nation’s affordability problems result more from low incomes confronting high housing prices rather than from housing shortages,” McClure said. “This condition suggests that we cannot build our way to housing affordability. We need to address price levels and income levels to help low-income households afford the housing that already exists, rather than increasing the supply in the hope that prices will subside.”

Longhofer sees the opposite.

“This is a supply-side problem,” Longhofer said. “Doing things that would make people able to buy houses exacerbates the problem. It doesn’t fix it. Subsidies to people for down payment assistance, subsidies for people to reduce the cost of the mortgage. All those would all actually make the problem worse, not better, because we’d increase demand.”

What kind of building to prioritize?Other critics of the status quo want to see communities approach building differently.

One of them, Charles Marohn of Strong Towns, spoke in Wichita earlier this year. His nonpartisan nonprofit advocates for a change to development patterns. While Marohn wants to rein in zoning barriers to affordable housing, he’s skeptical that communities can do so through big developments.

Instead, he encourages communities to create their own affordable housing by encouraging incremental development, such as residents adding smaller units to their existing homes.

Building permit data suggests that Wichita has already been trending in a Strong Towns-friendly direction, which prioritizes adding housing to the urban core over sprawling suburbs. Most home building still takes place in the city’s suburban-like ZIP codes, but building there has dropped significantly in most places.

While more additions would help, Longhofer said cheap land limits the Strong Town’s approach in Wichita.

“You don’t want to discourage that sort of thing,” he said. “But where that makes the most sense is in communities where land values are incredibly high.”

There’s also a downside to letting neighborhoods become too diverse in housing styles. Too many inconsistencies can undercut a neighborhood’s home values and stability over time, Longhofer said.

“When we complain about NIMBYism – which I’m a big complainer of NIMBYism – we do actually have to recognize there are reasons it came about, and that’s one of the pieces that is at tension with the proposals that he (Marohn) had,” Longhofer said.

Indeed, officials such as Labrum, the director of the building department, see a place for zoning restrictions at a time when they’re being rolled back in other places.

In 2009, the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, began a series of policy changes to promote housing that culminated with it becoming the first major U.S. city to stop limiting certain residential areas to single-family homes. Montana is pursuing its own regulatory changes to create the conditions for more housing to be developed to meet high demand and stave off rapidly rising housing costs.

Labrum worries though that too little zoning could be a legal nightmare. Accessory dwelling units can be great when done right, but what happens when they are not?

“I get nervous when we talk about just removing restrictions, but I really support and want to do those things,” Labrum said.

Filling the missing middleNo one foresees a population boom on Wichita’s horizon. But Longhofer said two other trends can increase housing demand in a slow-growing city.

“One of them is that average household size continues to decrease over decades,” he said.

Between the 2000 and 2020 censuses, Longhofer noted, the average household size declined from about 2.6 people per household to about 2.5.

“That doesn’t sound like a big difference,” Longhofer said, but the change means you need more structures to house the same amount of people.

“The other thing that people often fail to take into account is the obsolescence of older housing stock,” Longhofer said.

But developers haven’t been building new units to replace deteriorating or aging housing. When new-home construction flatlined as an outgrowth of the 2008 financial crisis, it left a gap in housing supply that Wichita is having trouble re-stocking. Right now, it’s very difficult for a new-home builder to construct something that sells for less than $350,000.

“The least expensive of the new-home market that’s being built often ends up becoming the middle-market, existing home five, 10, 15 years later,” Longhofer said. “You can’t build new homes for people who want something under $150,000 a year. It’s not possible.”

To fill the missing middle, the community will have to get a housing product built that wasn’t constructed the first time around, as it was in the past.

“When we think about the housing challenges that we have now, especially in the middle-market homes, it’s the homes that we didn’t build – from about 2008 to at least 2015, but even going closer to 2020 – it’s those homes that we weren’t building,” Longhofer said. “Those would be those middle-market homes that are not available in the existing home market now.”

No place like home

Feeling the pressure to find a new place to settle into in Wichita, the Beauchamps initially settled on a house that needed a layout change. They kept looking, though, just in case it fell through. Then, they toured a three-bed, two-and-a-half-bath house on a quiet east Wichita cul-de-sac.

In late May, it became their home.

The house had been on the market for 78 days, more than double the average listing length in Wichita. Built in 1992, its previous owners listed it for $249,000 — more than $50,000 over its taxed value.

The Beauchamps purchased it for $230,000, unfazed by the bright blue facade that may have chased off other buyers. It’s not their favorite color either. But Natalie Beauchamp said they’ll repaint it. The property is also missing a fence for the dog that Alex Beauchamp hopes to eventually have. The basement spaces need work. New kitchen cabinets could be in order.

But they’ve crossed a threshold so many in this city haven’t. It’s a change that, even amongst the packing of boxes and moving of dressers, Alex Beauchamp felt grateful for.

“It’s surreal,” he said. “Like when you walk outside and look around at a beautiful sunset.”

How we did this story

To better understand a driver of Wichita’s housing shortage, the Wichita Journalism Collaborative spent parts of the last year examining building patterns across the city. With the help of data journalist Janelle O’Dea, collaborative partners sought out 20 years of building permit data from the Metropolitan Area Building and Construction Department and analyzed it, filtering records and building pivot tables to better understand trends in residential construction.

The data showed a precipitous drop in home building following the Great Recession from which the city never fully recovered. The data provided a stark picture of how a lack of building is contributing to Wichita’s housing shortage. But the analysis raised questions about which builders were constructing fewer homes and whether some had left the market entirely.

We approached the building and construction department about obtaining a list of building permit applicants in hopes of identifying builders we could interview to understand why they were building fewer homes. Initially, there were questions about whether this data could be shared under the Kansas Open Records Act, since agencies are not required to create reports to fulfill requests for information.

The building department was able to find a way to provide the list of building permit applicants between 2000 and 2024. O’Dea created a script that converted the data into a format that could be analyzed more easily, which allowed us to see changes in who is building homes in Wichita over time. We used that list to contact more than a dozen of the most prolific builders in Wichita to request interviews about changes in their activity.

In addition to O’Dea, whose data work on this story was funded by the Wichita Foundation, former KMUW reporter Celia Hack served as a thought partner in developing and advancing this reporting.

This article was provided through the Wichita Journalism Collaborative, a partnership of 10 media and community partners, including KMUW.