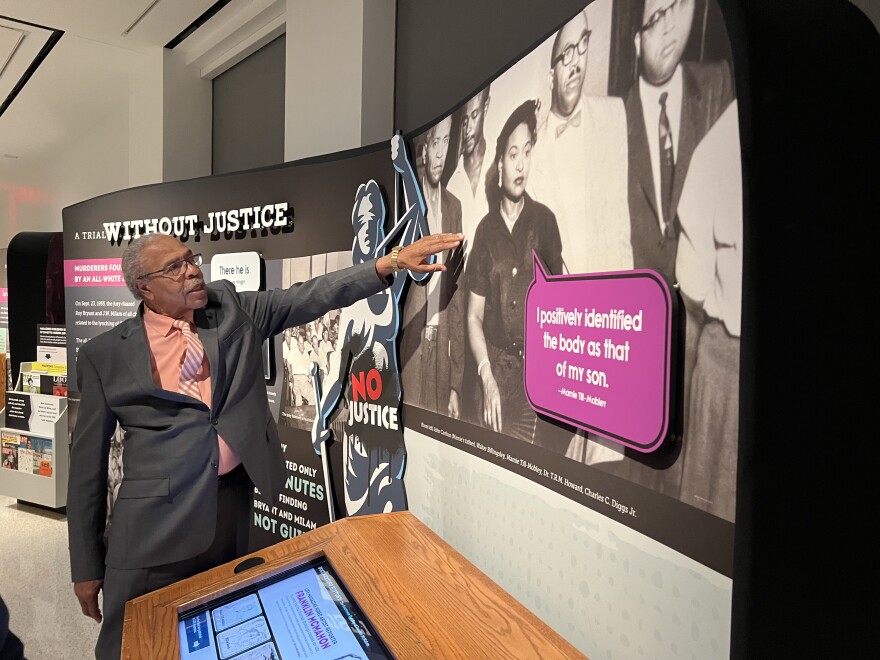

"This exhibit, to have it here, you have to be progressive," Rev. Wheeler Parker says as he shares his thoughts with reporters inside KU's Spencer Art Museum. He's 85 now and remembers being 16 when his life completely changed. Much of that experience is in the exhibit.

"To bring this exhibit here, to expose it like this, because it's not a pleasant story and some people say, 'Don't tell it, don't show it...' Because we are doing what? Much better? And we are — we've made progress — but you need to tell the story."

The story is of his cousin and best friend, Emmett Till. In 1955, a 14-year-old Black teenager from Chicago was abducted and brutally murdered while visiting relatives in Mississippi after whistling at a white woman.

"If we could have disappeared into the earth, we would have disappeared. We that knew the south, we that knew the morays of the south, we that knew the people of the south — when he whistled — we just all made a beeline for the car. Nobody said, 'Let's go.' Nobody said, 'Let's get out of here.' We just made a beeline for the car."

Parker says Emmett was a prankster, a fun-loving teenager — always trying to make people laugh.

"He sees that we are alarmed, now he is alarmed at what he has done," Parker says.

Days later, Parker remembers two white men entering the family's home, and into his bedroom.

"No lights on anywhere...dark as [a] thousand midnights, [they had] a pistol in one hand and a flashlight in the other," he says. "I closed my eyes to die, to be shot, and opened my eyes...I hadn't been shot and they were just going by to my right."

Looking for Emmett, Parker thinks they may have told Emmett to put on his shoes, but he wanted to put on his socks first.

"Whatever it was, he was not giving the right answers and it was just pure hell. You don't want to ever experience anything like that in your life. Emmett had no idea where he was, [or] who he was dealing with. He went peacefully with them, and that's the last time we saw him alive."

Till's murder and his mother's insistence on an open-casket funeral back in his hometown of Chicago — brought national attention to the violence and racism Black people faced in the South. Thousands also saw images of Till's mutilated body in Black publications. Knowledge of Till's death — and the acquittal of the killers — sparked support for the Civil Rights Movement.

"It was a whole different atmosphere and a whole different attitude," Parker says. "We've come a long way and we got a lot of work to do though. Thank God for the people who had the fire in their belly to help you."

One of the focal points of the exhibit is a lavender historical marker riddled with bullet holes. It was the third marker installed at the location in Mississippi where Till's body was removed from the Tallahatchie River.

"Bullet holes in a sign tell a story. It speaks volume[s]. Remind[s] you of where you are at, how much work we have to do and we just thank God now; very aware and conscious that we have diversity in going forth with these problems."

Patrick Weems is executive director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Mississippi. He looks over at the marker on display. He remembers when it was installed by the river in 2018.

"We had just put this sign up and it was beautiful. It was the third sign but it was fully restored, and then 35 days later, it got shot up. We didn't know who did it, and then six months later we found out it was students from Old Miss who had posted it on their social media; proud that they had done it and nothing ever happened to them. ...To be able to then create an entire exhibit around the continued violence — around just telling a 14-year-old Black child's story — this is what needed to happen, and we are not done. This is not a story in 1955. This story continues."

The first marker was pulled up, thrown into the river and never recovered. The second marker, covered with 317 bullet holes, is at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in DC. And the third marker is part of the traveling exhibit in Lawrence. After the third sign was vandalized, Weems says a bulletproof marker was put in its place.

"We got support from all around the country to replace it and it's like 400 pounds. We eventually put cameras up around it. The cameras caught a white supremacist group coming out there to film a propaganda video and so it deterred them from doing anything to it. Now it's a national park [and] it's owned by the federal government. President Biden declared it part of a national monument. ...It will be federally protected forever."

Parker says after nearly 70 years he still carries the impact of that experience, the terror, with him. He mourns the death of his friend and cousin, Emmett Till, but says he won't let hatred take over.

"We can't afford the luxury of hate," he says. "Can you imagine waking up in the morning...'[I] hate everybody. Hate Black folk. Hate red people.' Hate destroys the hater. I can't afford hate."

The exhibit will be on display at the Spencer Museum of Art in Lawrence through May 19.