One detail was unspoken during the Wichita City Council’s recent debate over stronger enforcement of an ordinance against homeless encampments:

Cleanups are far more frequent than they were prior to the updated ordinance, according to a Journal analysis of public records, and they have been occurring, on average, at least daily since stricter enforcement began in March.

After the council voted to crack down on illegal camping in the city last December, formal encampment cleanups are up from an average of 14 a month to 38 a month – a 171% increase compared to last year.

Despite the acceleration, some council members are dissatisfied. Mayor Lily Wu unexpectedly expressed her frustrations with visible homelessness at a recent City Council workshop.

The mayor was met with pushback from other council members and the chief of police, who pointed out the lack of available resources for those being displaced.

Wu, who’s also a board member of Second Light, the city homeless campus under construction, said an additional team should be added to make first contact with camps instead of police officers. City housing workers and service providers in the Sedgwick County Coalition to End Homelessness already make frequent visits to known encampments to connect them with resources.

Since the beginning of the year, at least 353 “homeless remediation work orders” have resulted in encampments being removed by the city Department of Park and Recreation, far outpacing the pace of the previous two years.

At the same time, 911 calls and nuisance submissions about visible homelessness have significantly climbed, with thousands of reports coming from residents. On top of that, unsheltered homelessness in Wichita is also steadily increasing, according to Point-in-Time count data.

When presented with these findings, Wu remained supportive of increased enforcement, writing in an email that it’s inhumane for people to live on the sidewalk and that it’s not fair to taxpayers.

“Enforcement should be an encouragement to go to a place like Second Light or Union Rescue Mission,” she wrote. “Handouts at street corners, for example, jeopardize the success of the nearly $30 million public investment into Second Light. We are encouraging people to donate to these nonprofit organizations and discouraging handouts at street corners with the “Real Change, Not Spare Change” campaign.”

Wichita officials have quietly been doing more for months, according to records. But there’s no evidence in yearly counts that their approach is decreasing homelessness. People are forced to leave, but then their camps come back – sometimes in the same spot, sometimes in another. The resettlements generate more frustration, with callers demanding even more sweeps, but the problem disappears only temporarily.

Officer Nathan Schwiethale of Wichita Police’s Homeless Outreach Team said that about 95% of homeless Wichitans living outside decline shelter but accept housing. One way to break the cycle could be drawn from a plethora of research showing that investments in housing over encampment removals — and the citations or arrests that come with them — regularly show a decrease in homelessness.

That long-term investment has yet to come to fruition in Wichita. In the short-term, the brunt of the messy work is on the shoulders of two municipal departments: the Park and Recreation Department and the Wichita Police Department, including its Homeless Outreach Team.

Both of those departments have been part of the emergency homeless response system for years — a cluster that includes city housing, service providers and private contractors — but this year is the first that the two departments have full responsibility for addressing and removing encampments, a change that came with the updated ordinance.

Gary Farris, a division manager in the park department, admits it’s uncomfortable to face a person whose belongings and camp are being involuntarily moved. But the department sees its work as a service to the community’s health.

“There’s a lot of really ugly and nasty parts that go along with this job … seemingly inhumane, the way that some of these people are existing. It’s tragic for them. They may not feel like it’s tragic, and you know, who am I, right, to judge them? But it just seems like it’s tragic,” Farris said, adding that at many sites his department cleans up human waste or needles and syringes, presumably from drug use.

“What we try to do is return the space back to a publicly accessible, usable and safe space for everyone," he said. "It’s impolite to talk about, but, you know, I hope nothing more for these people than to get the help that they need, that they want and that they can use to have a better life. That’s what I want for them. What my job is, is to clean up after the issue."

The Park and Recreation Department spent over $268,000 to buy tools and personal protective equipment in preparation for increased enforcement.

A hefty cost upfront, but the decision to move away from using private contractors is cutting the expenses associated with encampment cleanups — a fiscally savvy choice in a period of increased enforcement.

According to records, the city paid private contractors nearly $338,000 in 2024 with a total cost of $523,57 on removing encampments. Compared to this year, the city is spending less: $153,847 so far, with an expected annual cost of $361,803, including staffing, fleet charges, fuel and other supplies.

Everything else, numbers wise, regarding homelessness seems to be on an incline. Data woven together from thousands of calls, complaints, camps and cleanups shows increasing pressure to address homelessness swiftly — but also humanely.

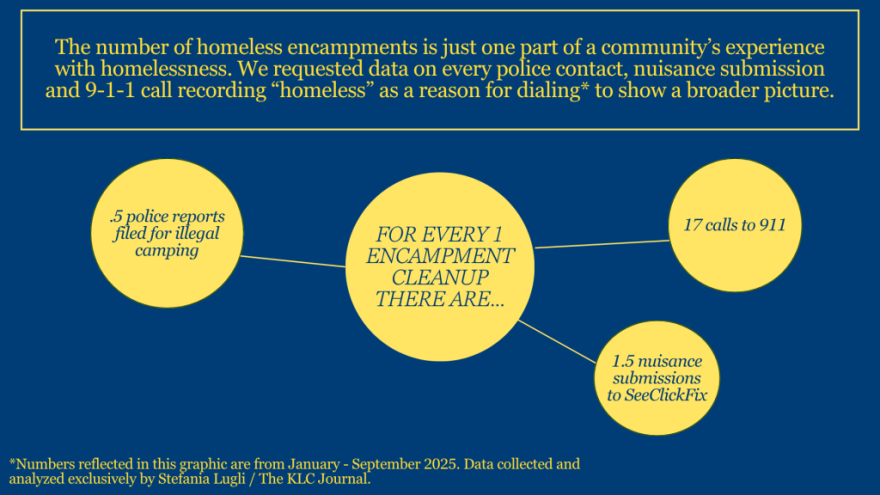

On average, for every homeless work order, there are 17 calls to 911 related to homelessness and 1.5 nuisance submissions on SeeClickFix. Encampments pop up all over the city, but the areas with the highest concentration for cleanups are downtown, the banks of the Arkansas River and along Kellogg Drive, data shows. The area around United Methodist Open Door, a day center for homeless resources, and Second Light’s campus also get frequent cleanups.

Capt. Jason Stephens, who oversees the Homeless Outreach Team, says that police contacts with encampments are largely complaint driven, with officers responding to calls citing camping, loitering, trespassing, panhandling or other issues.

Early this year, the police department updated internal policy to mirror language from the ordinance on how officers should interact with illegal campers and when to issue a citation. Each time an officer makes contact with someone illegally camping, a report should be completed. As of Sept. 4, 162 reports had been filed.

“The new policy does kind of stress that it’s every Wichita police officer’s responsibility and capability to address homelessness concerns, primarily the camping ordinance violations,” Stephens said. “Not every contact involves a cleanup, meaning that these guys and gals go out and address complaints, they make contact and get complete voluntary compliance from an individual who is willing to either receive services, move into the shelter, start working through the process of moving toward permanent housing, or at least voluntarily move the encampment to where it’s not that location.”

The Park Department then steps in, dispatching a four-person team to remove encampments. Most of the time, Park Director Reggie Davidson said, people who had been living in that spot have abandoned the area by the time a team arrives. If there are still people at the site, sometimes police are called to intervene in any conflict.

Unsheltered homelessness growing faster than overall

Wichita’s move to increase enforcement came months after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June 2024 allowing cities to enforce bans on homeless people sleeping outside and encampments, even if no shelter space is available.

The Wichita City Council’s 4-3 vote to lower the barrier for cleanups was adopted in December. Weeks afterward, Sedgwick County conducted its Point-in-Time count, an annual event required by the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department to survey the number of people experiencing homelessness. The results are largely considered an undercount of a community’s homeless population.

This year the county found 195 people experiencing unsheltered homelessness — the highest in recent history. It follows a national trend, concurrent with the nation’s affordable housing crisis and weakening social safety nets.

While overall homelessness in the county remained mostly level, the number of unsheltered people has significantly increased every year since 2019. The 195 counted in 2025 is more than triple the number of unsheltered people found in 2019.

Shelter beds have yet to keep up with the demand.

Some year-round shelters have closed while others operated temporarily in the winter. Second Light, the city’s developing, permanent homeless resources campus, will eventually operate with 220 beds, but while it’s under construction it has 125 beds for men and 69 for women.

A camp’s appearance is likely more grating to the average resident, compared to the hundreds of homeless Wichitans who are in some type of shelter. The visibility is the problem.

“(The unsheltered) are the candidates that we as a team are required to address. We’re looking at almost a tripling effect in the number of camps. The concerns from people are from seeing (homelessness) more,” Schwiethale, of the Homeless Outreach Team, said. He added that when he first wrote internal policy to address illegal camping a decade ago, others were confused at his initiative, saying that there weren’t enough tents to justify the policy.

Officer Ryan Oliphant, on the Homeless Outreach Team, said that despite being on it for only about a year, he, too, is seeing more and more camps.

“If you look back five years ago, the amount of tents that you would see just out on a drive — you didn’t see a whole lot of that. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon to have a two-mile drive to the grocery store and you may see one to five tents,” Oliphant said.

Regardless of why Wichitans want to see fewer homeless people, city officials are facing intensifying pressure. Thousands of calls and complaints clog the city’s response system while hundreds of people wait for housing or a shelter they feel safe to go to.

Until those resources are more supported, data suggests that hundreds of homeless Wichitans, and those who live alongside them, seem stuck in a cycle without a remedy.

Stefania Lugli is a reporter for The Journal, published by the Kansas Leadership Center. She focuses on covering issues related to homelessness in Wichita and across Kansas. She can be reached via email slugli@kansasleadershipcenter.org.

The story is part of the Wichita Journalism Collaborative, a coalition of newsrooms and community partners — including KMUW — working together to help meet news and information needs in and around Wichita.