Most people in the 1970s wore blue jeans — they were “the student dress code of the time,” says retired University of Kansas professor Katherine Rose-Mockry.

So when an unofficial student organization at the school advertised a “Wear Blue Jeans if You’re Gay Day,” classmates had a range of reactions.

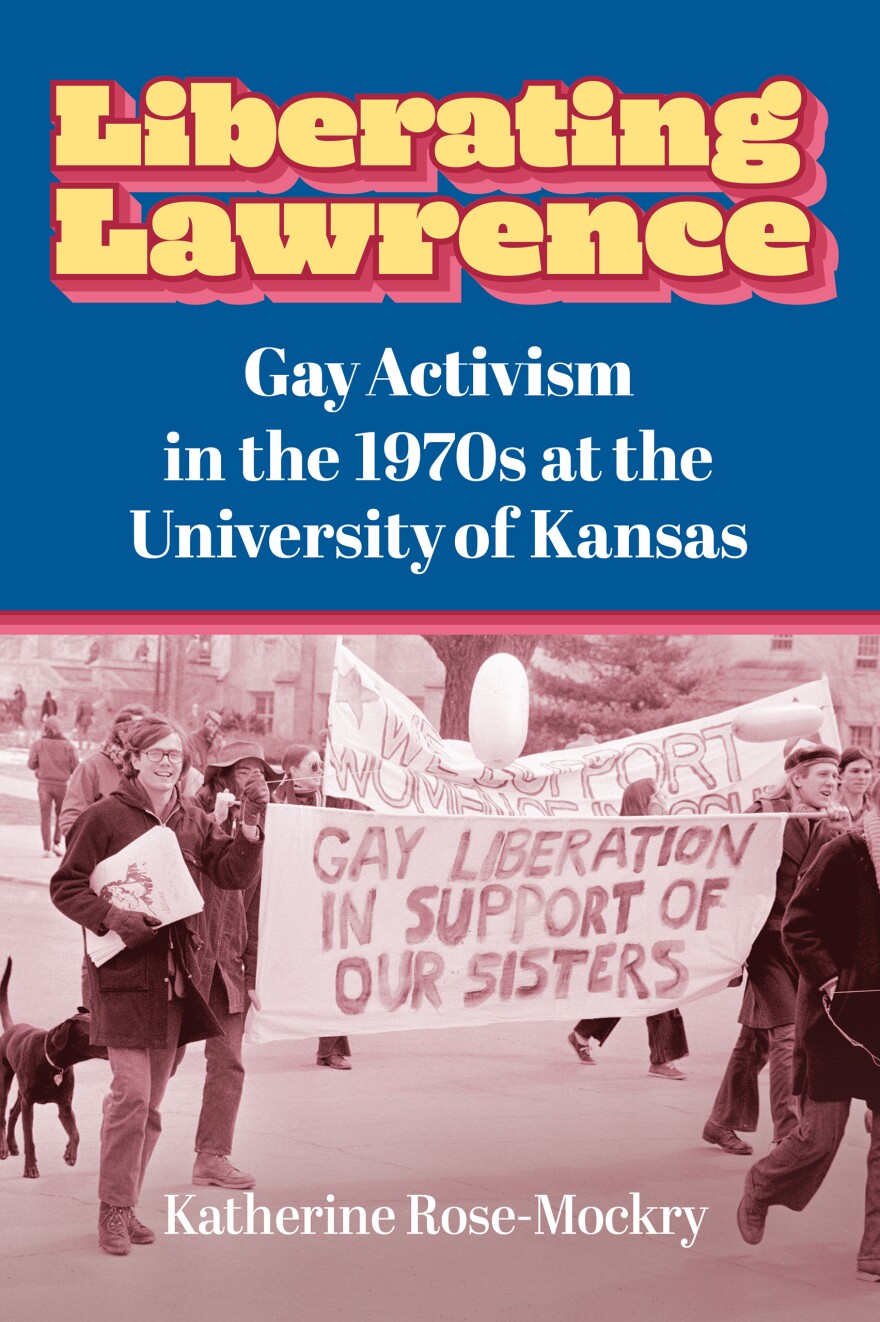

“It was a really controversial action,” says Rose-Mockry, whose book, “Liberating Lawrence: Gay Activism in the 1970s at the University of Kansas,” tells the story of the Lawrence Gay Liberation Front, which was active under various names from 1970 until 2016.

“Students were like, ‘I don't want to be identified as gay — oh no!’” she says. “Some students thought it was just the best.”

That’s what made it such a clever idea, Rose-Mockry explains. It forced people to inspect their concern for being identified as gay.

“Because it really challenged the feeling at the time about what's normal,” she says.

Rose-Mockry, who led the Emily Taylor Center for Women and Gender Equity at KU for 20 years and worked at the University of California, Los Angeles Women’s Resource Center for 14, began the book in 2010 as a dissertation.

“People I have worked with over my 34 years have identified in the LGBTQ+ group, and some of the stories I've heard have been heartbreaking, some have been uplifting and joyful,” she says. “I felt like it was important to make that story visible, because it really wasn't on our campus.”

David Stout, the founder of the Lawrence Gay Liberation Front, created a grant to make sure KU’s place in the national gay liberation movement was researched and documented while he and other activists were still around to share their stories.

Rose-Mockry and Stout initially identified dozens of former students to interview. Then, through what Stout referred to as the “gay grapevine,” the number climbed to 199. As she piggybacked on her dissertation and began research for the book, Rose-Mockry interviewed 66 from the list.

What she heard were stories the group had only passed down internally, and roadblocks members of the community ran into 50 years ago — “how far we have come, and how far we haven’t come,” Rose-Mockry says.

“Without these stories, you lose the context, and there's no way of recognizing what has happened and what has not.”

One troubling story, recalled by multiple people, involved the difficulty gay students went through trying to gather professional and academic references.

A young man from Wichita, for instance, reached the end of his coursework for a teaching degree, but depended on positive references to keep moving forward.

“If your department said, ‘Oh no, this person has bad character’ — and they don't even need to explain what they meant by that — somebody could be closed off from being a teacher, being an attorney, being a doctor, being a social worker, any of those things,” Rose-Mockry says.

The fight for recognition

Prejudice also kept the Lawrence Gay Liberation Front from official recognition on campus for its first 10 years, locking it out of some funding and the use of campus spaces.

In the late 1960s, Stout had done his own research for a social welfare class interviewing gay and lesbian students in Kansas City, Lawrence and Topeka. Once the assignment was in, another student insisted Stout continue the work; LGBTQ+ groups were popping up all over the country, and Kansas didn’t have one.

The student put fliers all over Lawrence advertising a gathering, and listed Stout as the contact.

Attending meetings was risky in the 1970s, but those who did felt less alone and began deploying methods — like Wear Blue Jeans if You’re Gay Day — to advance gay rights and help other queer students feel more comfortable.

KU’s administration didn’t like it.

The first time the LGLF applied for official recognition, with support of the student senate, then-Chancellor Laurence Chalmers overrode their endorsement.

The second time they applied, Chalmers did the same.

“It was because of ‘sexual proclivities’ — a word that really is only used related to the gay community,” according to Rose-Mockry. “The chancellor said their actions were against the law, but they weren't having sex in their meetings, so why would that apply?”

When the same thing happened on their third try, the group filed a complaint with the university, then filed a lawsuit.

The LGLF didn’t win in court, but their legal fight generated the visibility students needed to connect with regional and national activists. They hosted a popular dance night on campus, members wrote for a gay newspaper, and the group’s house provided a waystation for like-minded travelers.

Rose-Mockry sees their legacy on campus as being largely about educating the general population, which has won them a lot of allies.

“It was the visibility, the collaboration, and the open-arms attitude they had,” she says. “‘Come and get to know us,’ rather than … ‘If you aren't with us, you're against us.’”

This story was produced in partnership with the Kansas City Public Library.