Monrovia, Liberia's capital, is a city that relies on public transportation — buses, private vans (also known locally as buses), cars and motorcycle taxis. And you can't use any of these options without coming into contact with other people, whether you're jostling in line or wrapping your arms around a motorcycle taxi driver.

Since the Ebola outbreak, Monrovia has placed new restrictions on public transport, and fewer drivers are willing to take chances. So there aren't as many options for commuters at a time when Ebola has made everyone afraid of touching strangers.

Getting around Monrovia is difficult in the best of times. Passengers now wait for hours for private vans to show up, and then must brave a crush of people, and the risk of contact, to try and get a seat.

The government has forced taxi drivers to limit the number of passengers they can carry to three people in the back seat — to limit the risk of touching. Before they would squeeze in four, five, even six passengers. There's no way of knowing which ones might have Ebola. Motorcycle taxi drivers, who usually get much of their business from students, are finding it almost impossible to find fares. Schools have been closed since the summer.

We asked Monrovians how they are dealing with transportation — and the possibility of contact with others.

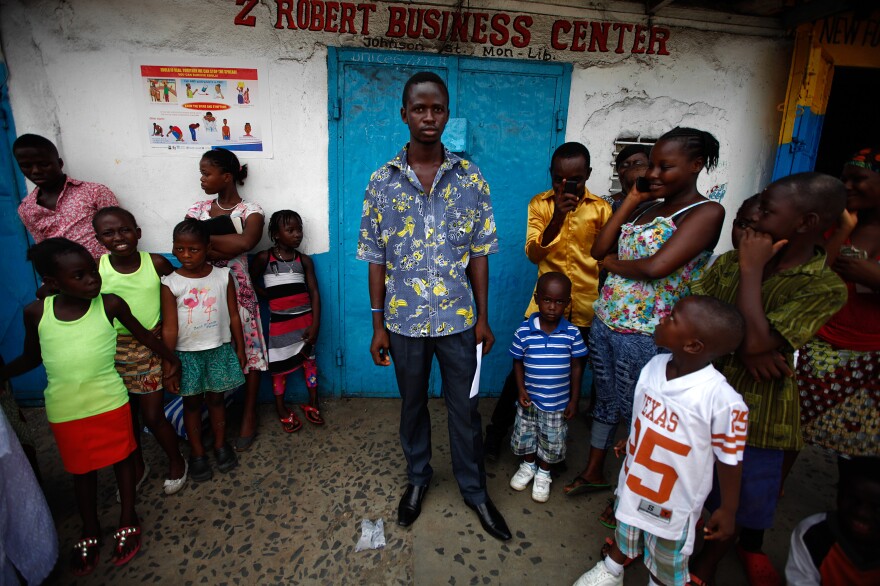

Alieu Massaly (below): Before the Ebola epidemic began, motorcycle taxi driver Massaly would wait just five minutes between passengers. Now it's two hours. And while he worries about his passengers touching and infecting him — he knows two friends of friends who have died from Ebola — he says he can't quit his job. He needs the money. "I feel bad, but what to do? No other way in this country to get money."

Enoch Herring (below): Although cab drivers have died in the epidemic after transporting sick people in their cars, Herring is still driving. "These people are our citizens. It is my duty." He says it's like being afraid of a ghost you can't see. His girlfriend worries he'll get Ebola, but he's being careful. He won't pick up anyone who looks sick, he washes his car and his body with chlorine every day — and he prays. "You have to keep the faith. It's just about faith."

Koyapo Kannes (below): When a bus pulls up across from where Kannes and her sister are waiting, they don't even try to get on. "Everyone runs, all the men in front. You have to push to get in." Even after an hour of waiting, Kannes doesn't want to push through the crowd of men jostling around the first private van that shows up. "No touching. Ebola is real. It is killing our people."

Anthony Gboye (below): Gboye is saving up for medical school. Since the epidemic began, his bus fare has more than doubled. But there are few alternatives. "Before, if you see a friend in traffic, they will give you a lift. But now, people are not accepting their friends because of Ebola." It happened to him: A friend saw him and just kept driving.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.