The FBI agent was unsparing — and pessimistic — in an assessment of the Kansas City, Kansas, Police Department.

KCKPD officers routinely violated the civil rights of those they were sworn to protect. They severely beat people in the city jail. They were alleged to have been dealing illegal drugs and committing robberies. And they ignored the crack cocaine epidemic in Wyandotte County.

“The problem is as bad as it is because of corruption within the police department and general investigative incompetence,” the FBI agent wrote.

Those findings were memorialized in a memo dated Dec. 18, 1992, by a special agent of the FBI, whose name was redacted, as part of an investigation into corruption within KCKPD that went under the code name “Operation Street Smart.”

The memo was obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request to the FBI for records of its past investigations into the KCKPD.

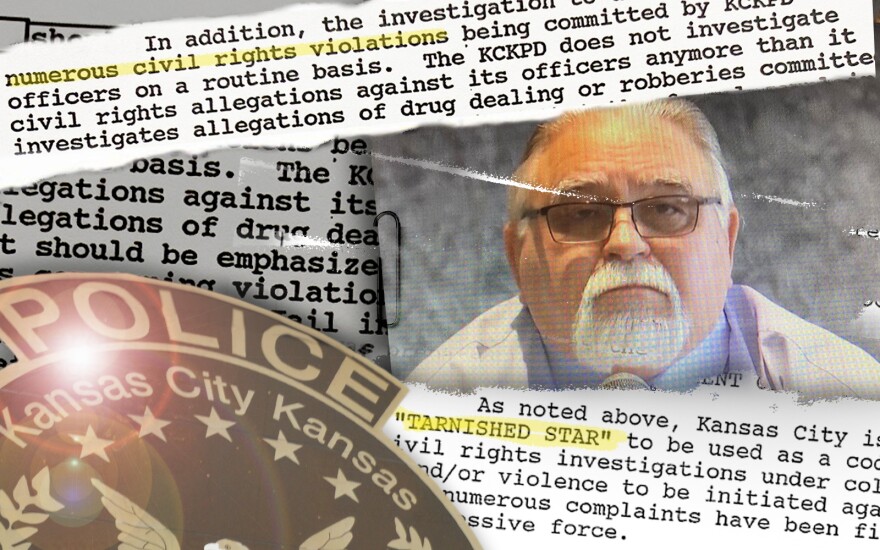

Nearly 30 years later, the department is making headlines with reports of a federal investigation into alleged corruption. Former KCKPD detective Roger Golubski is accused in a civil case of systematically preying on Black women to satisfy his sexual proclivities or to fabricate evidence to clear cases. He is also accused of protecting drug dealers.

The news reports marked a rare public disclosure of a federal probe into some aspect of the KCKPD.

But as records obtained from the FOIA request show, the FBI has known corruption within KCKPD “has existed for decades.” And the agency appeared to have been frustrated at times by a lack of resources and inertia from the U.S. Attorney’s office in Kansas in responding to FBI discoveries about the department.

“The situation did not develop overnight, and it will not be solved overnight,” the memo reads. “The FBI has never convicted any KCKPD officer of any crime. Until this office does convict several police officers and hopefully gain the cooperation of some of these police officers, the situation in Kansas City, Kansas, will only deteriorate.”

Shown the documents, KCKPD spokesperson Nancy Chartrand said there are only 12 officers currently at the department who were employed there in 1992, half of them new recruits that year. The others had been working for the department for fewer than four years by 1992.

“That being said, it is impossible to validate nor negate the findings of that period in 1992,” Chartrand said in an email.

Asked if the depiction of the KCKPD in the FBI records reflects the department as it exists today, Chartrand said it does not. She cited several national developments that have triggered long-term police reforms, such as the beating of Rodney King in 1991, the use of DNA in forensic investigations and the growing use of dashboard and body-worn cameras.

“Simply stated, policing in our country has changed significantly over the past 29 years,” she said.

The FBI’s investigation of the KCKPD during the early 1990s turned up several incidents of alleged excessive force and brutality by police officers.

One memo from 1993 to FBI headquarters said there were 200 officers accused of misconduct. Some had one complaint of excessive force against them. Others had between eight and 17 excessive force complaints over a three-year period.

The Kansas City FBI office and the U.S. Attorney identified 18 officers who made up the “core group” due to the numerous amounts of excessive force and conduct complaints against them. All the names were redacted from the records. In order to investigate the allegations, the FBI estimated it would take at least four agents working full time for the “next 6 to 12 months or longer.”

“The KCKPD does not investigate civil rights violations against its officers anymore than it investigates allegations of drug dealing or robberies committed by officers,” the report said. “It should be emphasized that the formal complaints made by citizens concerning violations of their civil rights is only the tip of the iceberg.”

Chester Owens, the first African American city councilman in Kansas City, Kansas, when he was elected in 1983, said he’s been fighting police brutality for decades. He believes the majority of officers are good, but there are still bullies who often pick up racist behavior as part of officer training.

“I think the difference of then and now (is) back then, some of them just took it on their own to do stuff,” Owens said. “But now they’ve put it in form and trained them.”

One incident from a memo dated April 22, 1993, described a disturbance near 7th and Troup streets in northeast Kansas City, Kansas. (The date it occurred is unclear; the FBI records redacted names, dates and other details of the incidents it recounted.)

The memo said several young people accused an officer of stepping on the back of an unnamed person, kicking a person in the ribs, using profanity and epithets including the n-word and striking a person on the head with a gun. The summary of the incident said no significant injury resulted.

“The police officer is white, and remarks were made which could indicate a lack of sensitivity on the officer’s part to the black children,” the memo stated. “If it is determined that this matter should be investigated, at least 25 interviews will be required.”

A description of a similar incident was detailed in a written complaint by the NAACP legal department. The letter, according to FBI records, said that a group of 16 Black children between the ages of 7 and 16 were walking to a relative’s house on a rainy day when six white officers stopped them.

The officers searched the children and ordered them to the ground; some of them were lying in mud.

“When one of the older cousins questioned why the police were doing this and asked what they had done wrong, one of the officers proceeded to hit him with his gun and repeatedly kick him with his shoes,” the FBI summary of the NAACP’s complaint said. “Another cousin was then thrown over the fence by another officer, and the officer proceeded to beat him.”

One of the officers whose name is redacted from the report admitted to being at the scene but denied hitting or kicking any of the kids. The incident resulted in the officer receiving a “counseling form” that said the officer could have allowed the children to get out of the rain sooner once he found out there were no weapons.

“Officer [name redacted] was told that in the near future, in inclement weather such as this, he should use a little more tact in handling this type of a call,” the FBI record said.

A 1993 FBI memo said many people who filed complaints against the KCKPD did not follow up, which the FBI concluded was probably because they didn't believe anything would be done and they feared they may not be seen as credible witnesses. The memo also said there was strong cohesiveness among police officers and it would be difficult to find an officer who would testify against another officer. The FBI also thought many of the complaints reflected proper police protocol.

In an interview with KCUR nearly two years ago, FBI agent Al Jennerich, who investigated the KCKPD during the 1990s, backed up the FBI records.

To investigate that many officers in a small department was unusual, Jennerich said, adding that he was shocked at some of the KCKPD procedures, including the destruction of internal affairs reports after just three years.

“Now why would you do that? The only reason you do that would be to protect dirty cops or cops that are behaving improperly,” he said.

Jennerich recalled that a couple of officers were indicted.

An officer who faced charges was Edward Dryden. He was among several defendants charged in 1993 with a conspiracy to distribute crack cocaine.

Dryden, then a 25-year veteran of the police department, was accused of being involved in the drug operation and of tipping off other defendants of impending arrests against them.

Dryden, a Black man who died in 2019, was convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

In another case, in 1994, a KCKPD officer was indicted by a federal grand jury less than a month after FBI agents arrested him for possessing and intending to distribute illegal steroids, according to an article in the Kansas City Kansan newspaper.

But the U.S. Attorney’s office in Kansas wasn’t interested in pursuing such cases after then assistant U.S. Attorney Julie Robinson, who had championed the FBI’s work, left the office, he said. Robinson was appointed a federal bankruptcy judge in 1996 and is now a U.S. District judge in Kansas City, Kansas.

A standing monthly subpoena for KCKPD’s internal affairs reports was lifted after Robinson left the U.S. Attorney's office and KCKPD complained, Jennerich said.

“When Julie Robinson left, the cops over there, management, they saw that … it was a crack in the door and they decided they were going to go through that door basically to complain about the FBI investigating,” Jennerich said. “So no more subpoenas.”

Without the grand jury subpoenas, there could be no investigation, he said. Ultimately, the FBI also lost interest in the corruption cases, Jennerich said.

“The FBI does not want these cases,” he said. “It’s just a big headache for them politically.”

But at least one FBI agent was pushing for prosecutions of KCKPD officers in 1992.

“A more aggressive approach by this office in identifying and prosecuting police officers who routinely violate individuals’ civil rights would benefit this overall investigation,” the unnamed FBI agent wrote, “because the investigation to date has shown that many of the same officers involved in corruption are also involved in civil rights violations.”

An FBI memo from 1993 noted that a source for the agency had said some KCKPD officers would steal money and drugs from people they stopped in the streets.

Similar behavior landed KCKPD in the headlines in 2011 when members of a tactical squad were arrested and charged with stealing cash and electronics from residences where they were executing search warrants.

But public scrutiny of the department would not become widespread until the exoneration in 2017 of Lamonte McIntyre, a Black man in KCK who was convicted of a double-homicide in 1994.

Roger Golubski was one of the detectives who investigated McIntyre’s case.

After lengthy court proceedings, the Wyandotte County District Attorney in 2017 declared that a “manifest injustice” had occurred in McIntyre’s case, setting him free after 23 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

Since then, Golubski has been the main focus of a civil rights lawsuit filed by McIntyre and his mother against KCKPD officers and the Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, Kansas.

The lawsuit portrays Golubski as a crooked cop who took advantage of Black women in the poorest sections of KCK. He exploited Black women, some of whom were addicted to drugs and others who were sex workers, for sexual favors or to compromise them into fabricating testimony to help him clear cases he investigated, according to the lawsuit.

In court filings, Golubski has denied the allegations. In a deposition, he refused to address more than 500 questions posed to him by McIntyre’s legal team, citing his constitutional right against self-incrimination.

It’s not clear what aspects of Golubski’s alleged behavior have attracted the focus of the grand jury’s investigation. A CNN report, citing former KCKPD chief Terry Zeigler, said the grand jury issued subpoenas for about a dozen case files from the police department. Both KCKPD and the Unified Government have confirmed they received federal subpoenas.

The NPR Midwest Newsroom and KCUR filed a Kansas Open Records Act request for the subpoenas, which remains pending. Previous KORA requests for grand jury subpoenas were denied by the Unified Government on the grounds they were investigative records. But the UG has since publicly acknowledged the existence of the investigation.

Since the civil rights lawsuit was filed in 2019, McIntyre’s legal team has gone further to examine Golubski’s behavior as a KCKPD detective. Earlier this year, McIntyre’s lawyers went to a magistrate judge and demanded an order that the Unified Government turn over several sets of records.

Among the records they sought were investigative files about 18 women Golubski allegedly sexually exploited and used as informants. They also sought records of the investigations carried out by KCKPD into the murders of women Golubski had used as informants.

“A dozen or more of Golubski’s female victims and/or informants have been murdered,” reads a footnote in a filing by McIntyre’s lawyers. “With only a couple of exceptions, these murders remain unsolved. In some instances, Golubski was a primary investigator in the case, despite his past relationship with the informant.”

McIntyre’s lawyers also want KCKPD files related to drug dealers and gang leaders who had connections to Golubski. The lawyers said the records are necessary to establish KCKPD’s tolerance of misconduct by its officers.

The magistrate judge found most of the arguments by McIntyre’s lawyers persuasive and ordered the Unified Government to make the records available.

Social justice leaders in Kansas City, Kansas, applauded the Oct. 14 news of the federal grand jury probe into Golubski’s alleged crimes.

But they are also calling for a larger investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice into “systemic patterns and practices that have violated the civil rights of communities of color in Kansas City, Kansas.”

“For far too long the injustice perpetrated and covered up by the Kansas City, Kansas Police Department have gone ignored,” reads the online petition championed by MORE², a KCK social justice group.

Long quiet, victims’ families are now speaking up. Kendra Wright attended a MORE² rally on Oct. 25 in front of Kansas City, Kansas, City Hall. Wright is the niece of Rose Calvin, a woman with whom Golubski had ties and whose 1996 homicide remains unsolved.

“This man nearly destroyed us but we are strong and we are here,” Wright said.

Still, Wright said her family is hopeful.

“We are going to get justice,” she said. “We’re hoping that it’s going to be soon.”

Karl Oakman, a former deputy chief of the Kansas City, Missouri, Police Department, inherited the Golubski fallout when he became police chief in June.

Oakman recently said he plans to open a cold case unit in January, although said that Kansas City, Kansas, is not the only place that had a high number of unsolved homicides of women during the period in question. There were a large number of unsolved cases from the 1980s and1990s because of the nationwide crack cocaine epidemic, he said.

Still, Oakman said the cold case team will consist of three people who will look at the cases of the murdered women.

“We'll prioritize which cases that, for instance, if there's DNA evidence in this case, and there's not any in this case, what we're going to try to do is go with the case with the DNA and try to get, see if we can get a profile and maybe solve that case,” he said.

This story is part of a collaboration between KCUR and the Midwest Newsroom, an investigative journalism initiative including KCUR, IPR, Nebraska Public Media News, St. Louis Public Radio and NPR.

Copyright 2021 KCUR 89.3. To see more, visit KCUR 89.3. 9(MDA0NTM3OTcyMDEyNjIwNDkzMjFhNTlkZg004))